Building a diverse and robust training pipeline

At a glance

Issue

Almost 30 per cent of the Canadian population has some form of disability. However, people with disabilities make up only about 2 per cent of the academic researcher community. This imbalance illustrates the extent of barriers that are faced by persons with disabilities to fully participate in the health research funding system.

Research

The CIHR External Advisory Committee on Accessibility and Systemic Ableism was established in 2022 to provide guidance on how to make health research funding accessible to all researchers. As member of the Committee and a researcher with a disability, Dr. Emilio Alarcón at the University of Ottawa Heart Institute is providing valuable insights into the barriers facing researchers with disabilities and how to address them.

Impact

The Committee has provided CIHR with guidance on how to hold fully accessible meetings and develop accessible engagement materials. It also co-developed a chapter in the CIHR Accessibility Plan and is guiding the development of an anti-ableism action plan to further address ableism at CIHR and in the health research funding system.

Dr. Emilio Alarcón is passionate when it comes to fixing things that are broken. His groundbreaking research is developing novel biomedical materials to repair damaged heart, cornea, and skin tissue.

That passion includes fixing an educational system that falls short in creating welcoming and accessible environments for the almost one-third of people in Canada living with disabilities. They include individuals whose disabilities are not always obvious, such as mental illness, learning and attention issues, certain physical illnesses and neurodiversity.

“You’ll hear statistics like 22.5 per cent of Canadians live with a disability, but that number jumps to about 30 per cent when you include non-apparent disabilities, or what used to be called invisible disabilities,” said Alarcón, Director of the Bio-nanomaterials Chemistry and Engineering Laboratory at the University of Ottawa Heart Institute and Associate Professor, Department of Biochemistry, Microbiology and Immunology at the University of Ottawa.

Our differences make us stronger

As someone on the autism spectrum, Alarcón speaks from experience. As a child, he remembers being singled out as different because he could “taste” colours.

“Red tasted like cranberries and orange tasted like vanilla,” he recalled. “But society broke me down because they thought this was weird, so I learned not to do it anymore and sometimes I miss it very much. I want the next generation of students and researchers to not lose who they are and not worry about looking or sounding the same. Our differences are what make us stronger.”

That diversity, he stressed, also leads to better research and better outcomes. Yet, people with disabilities continue to comprise just 2 per cent of professors and researchers in post-secondary institutions. Alarcón is working on several fronts to make academia more diverse, including through his participation in the CIHR External Advisory Committee on Accessibility and Systemic Ableism.

“This underrepresentation in the academic and research ecosystem is a particular issue in health research because it perpetuates the idea of the medical model of disability,” explained Alarcón, who also has a son with both Down’s Syndrome and autism.

That model has traditionally viewed disability as an impairment or abnormality within an individual, rather than a difference like gender, age, or race. It focuses on curing the individual or making them appear less disabled, rather than addressing the systems and structures that contribute to an inaccessible society.

“It’s not about curing. It’s about bringing the voices of individuals with disabilities to the table so we can focus on providing a better quality of life,” he added. “And that requires approaches that are rooted in accessibility, not accommodation.”

Making academia accessible by default

This can include everything from making buildings more accessible for people using a wheelchair or living with a visual impairment. It also means challenging long-held academic traditions. Alarcón said these traditions reward "hyper productivity" with tenure and promotions. He added that faculty with a non-apparent disability may be reluctant to disclose their disability. They fear it might hinder their job security or career development.

“You shouldn’t have to disclose your disability for institutions to be fully accessible. Alarcón said, “They should be accessible for everyone by default.”

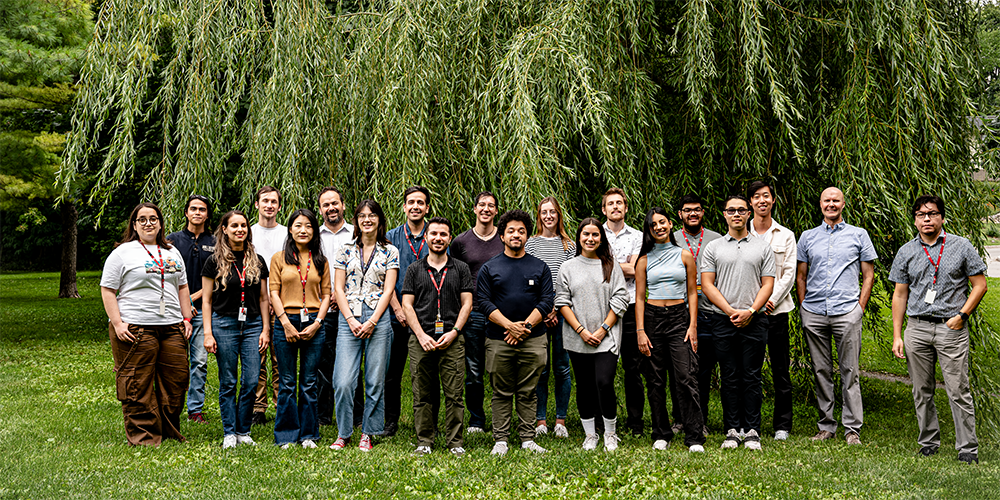

Alarcón’s efforts to make diversity and inclusion the norm in academia extends to other underrepresented groups, including women, Indigenous Peoples, racialized people and 2SLGBTQI+ persons. For example, he and Dr. Alison Flynn in the University of Ottawa’s Department of Chemistry and Biomolecular Sciences are leading the new INterdisciplinary Training in BIOmedical TECHnologies (INTBIOTECH), a $1.65-million program that puts equity, diversity and inclusion front and centre to build a robust pipeline of highly skilled professionals for a growing biomanufacturing sector.

“We’re changing the way we recruit and train people, working with our private and public sector partners to offer networking, internships and mentorship opportunities,” he said. “It’s not enough to hire a diverse team, you need to support that diversity throughout the training program.”

Alarcón also founded an innovative science talk radio program. It's called BEaTS Research Radio. It connects early-career scientists and investigators from different cultures, abilities, genders, and neurodiversity. They stream a weekly science podcast in multiple languages.

Alarcón is also leading the IDEAS (Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, Accessibility and Social Justice) Committee of the new Brain Heart Interconnectome (BHI). This interdisciplinary research program led by the University of Ottawa received $109 million from the Canada First Research Excellence Fund. In collaboration with patients and community partners, researchers from across Canada and diverse partner organizations, BHI will transform brain-heart research, prevention and care on a global scale.

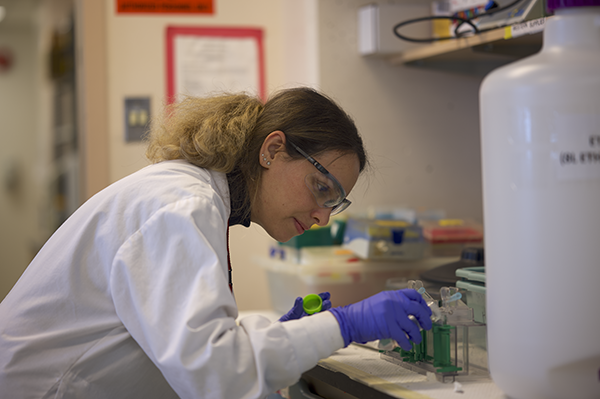

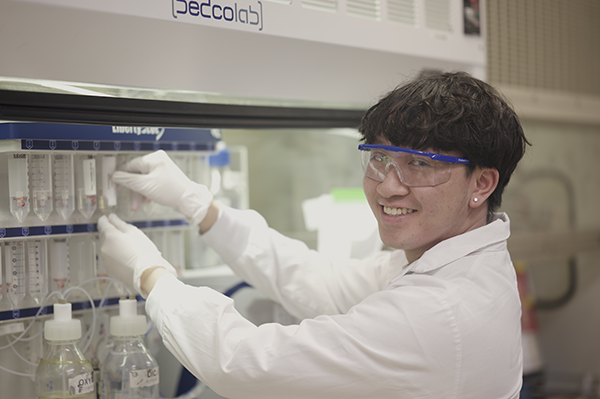

“It’s about creating an inclusive research ecosystem for everyone, including individuals with disabilities,” said Alarcón. “Put people first, not their supposed differences, and listen. I try to create this environment in my lab where students can be who they want to me. There is no one size fits all and that is instrumental in my research.”

- Date modified: