Post-Traumatic Stress Knowledge Gaps Consensus Workshop: What We Heard

Perspectives on Current Knowledge and Future Directions for Research

January 23 to 24, 2020

Ottawa, Ontario

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Workshop Objectives

- Agenda | January 23, 2020

- Agenda | January 24, 2020

- Executive Summary

- Summary of Workshop Sessions

- Contact us

Introduction

Post-traumatic stress (PTS) and related disorders are prevalent in many sectors of the Canadian population, and can have a tremendous impact on individuals, families and communities. New knowledge – and the effective translation and dissemination of that knowledge – is essential to inform policies and practices to improve outcomes for individuals living with PTS.

This two-day workshop was an important component of a developing research initiative for PTS being led by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Institute of Neurosciences, Mental Health and Addiction (CIHR-INMHA). It was carefully designed in partnership with people with lived and living experience (PWLE) of PTS, ensuring their voices were heard and incorporated throughout. This workshop also benefited from a diverse selection of participants, including researchers, policy makers, Indigenous Peoples, community members and other knowledge users, who shared their expertise and highlighted gaps in our collective understanding of PTS.

The ultimate goal of this knowledge gaps event was to discover what new knowledge is needed to inform better paths to wellness for individuals living with PTS, and their families and communities.

This report comprises a summary of what we heard at the workshop. It is intended to capture knowledge gaps that were highlighted at the event, with a particular emphasis on the expertise of PWLE. The workshop was framed around four main themes: Support, Indigenous Perspectives, Diagnosis, and Treatment; and the report structure mirrors the order of sessions during the workshop. To protect the anonymity of our PWLE participants, no names or affiliations are used in this report.

The meeting book for this workshop is available to the public upon request. Requests can be directed to: pts-spt@cihr-irsc.gc.ca.

Workshop Objectives

The primary objectives of the workshop were to:

- Bring together a diverse group of experts to identify gaps in our collective understanding of post-traumatic stress.

- Facilitate an open dialogue focused on the expertise of people with lived and living experience, so that their voices can inform future CIHR research and knowledge translation activities.

- Discuss how research can drive better outcomes for Canadians affected by trauma- and stressor-related disorders and their families.

Agenda | January 23, 2020

| Time (ET) | Item | Speakers |

|---|---|---|

12 p.m. to 1 p.m. |

Registration |

|

1 p.m. to 1:20 p.m. |

Elder Opening and Smudge |

Nokomis Jane Chartrand |

1:20 p.m. to 1:45 p.m. |

Welcome and Context Setting |

Dr. Samuel Weiss |

1:45 p.m. to 2:30 p.m. |

Opening Talk |

Douglas McLeod |

2:30 p.m. to 3 p.m. |

Refreshment Break |

|

3 p.m. to 4:35 p.m. |

Support PWLE Talks (30 mins) Science in Brief (10 mins) Open Discussion (30 mins) Recording Reflections (10 mins) |

Moderator: Dr. Suzette Bremault-Phillips Presenters: Catherine M., Andrea S., Mary Beaucage Presenter: Dr. Alexandra Heber |

4:35 p.m. to 4:45 p.m. |

Review and Preparations for Tomorrow |

Dr. Samuel Weiss |

4:45 p.m. to 5 p.m. |

Elder Closing |

Nokomis Jane Chartrand |

5:30 p.m. to 7:30 p.m. |

Reception and Networking Hosted by the Mental Health Commission of Canada |

|

Agenda | January 24, 2020

| Time (ET) | Item | Speakers |

|---|---|---|

7 a.m. to 8 a.m. |

Breakfast |

|

8 a.m. to 8:15 a.m. |

Elder Opening |

Grandmother Marjorie Beaucage, Elder Sally Webster |

8:15 a.m. to 8:30 a.m. |

Welcome and Review |

Dr. Samuel Weiss |

8:30 a.m. to 10:15 a.m. |

Indigenous Perspectives

|

Nokomis Jane Chartrand, Grandmother Marjorie Beaucage, Elder Sally Webster |

10:15 a.m. to 10:45 a.m. |

Refreshment Break |

|

10:45 a.m. to 12:05 p.m. |

Diagnosis PWLE Talks (30 mins) Science in Brief (10 mins) Open Discussion (30 mins) Recording Reflections (10 mins) |

Moderator: Dr. Nick Carleton Presenters: Fiona Haynes, Morgan Klein Presenter: Dr. Margaret McKinnon |

12:05 p.m. to 1 p.m. |

Lunch |

|

1 p.m. to 2:20 p.m. |

Treatment PWLE Talks (30 mins) Science in Brief (10 mins) Open Discussion (30 mins) Recording Reflections (10 mins) |

Moderator: Dr. Rakesh Jetly Presenters: Malek Amr, Ramona Bonwick, Alice Martin Presenter: Dr. Ruth Lanius |

2:20 p.m. to 2:40 p.m. |

Refreshment Break |

|

2:40 p.m. to 3:15 p.m. |

Identifying Overarching Themes |

Dr. Samuel Weiss |

3:15 p.m. to 3:30 p.m. |

Closing Remarks |

Dr. Samuel Weiss |

3:30 p.m. to 3:45 p.m. |

Elder Closing |

Nokomis Jane Chartrand |

Executive Summary

Below is a high-level summary outlining the major knowledge gaps that arose from the Post-Traumatic Stress (PTS) Knowledge Gaps Consensus Workshop, which was held Jan. 23-24, 2020, in Ottawa, Ontario. The workshop was designed to focus on the expertise and experiences of people with lived and living experience (PWLE) of PTS and was organized around four primary themes: Support, Indigenous Perspectives, Diagnosis, and Treatment. The goal of the workshop was to discover what new knowledge is needed to inform better paths to wellness for individuals living with PTS, and their families and communities.

Support

Frequently cited as a risk factor for the development of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), the need for adequate, appropriate support systems was mentioned throughout all four themes of the workshop.

The following types of support were highlighted:

Peer-to-Peer Support

Peers have shared perspectives and experiences, making them valuable sources of support for many population groups including veterans, public safety personnel (PSP), Indigenous populations and individuals with chronic illness. Internet-based peer support models can overcome geographical barriers and may be more comfortable for some individuals. Barriers to peer support include stigma around mental illness and access to appropriate, qualified support (either in-person or online).

Support Networks

Coordinated networks can facilitate peer-to-peer support opportunities by connecting individuals living with PTS with others who have similar experiences but are otherwise outside of their social circle. Peer support, and access to trauma-informed care, may be particularly relevant for individuals with chronic illness (e.g., cancer, multiple sclerosis, individuals who have had an organ transplant). In addition to support networks for individuals, there is also a need for support networks for family members and caregivers of individuals living with PTS, as well as for communities – particularly in rural/remote areas and/or in Indigenous communities.

Support for Reintegration Following Trauma

Certain groups, including PSP and veterans, have existing reintegration programs and processes that tend to focus on return to work, but may be insufficient. Successful reintegration may include desensitization training, peer-to-peer support, personalized treatment, problematic substance use treatment, and ensuring the privacy and confidentiality. Peer-led programs may be more effective than physician-led. The Critical Incident Reintegration Program developed for the Edmonton Police Service is an example of one such peer-led program.

Several barriers to support were identified.

Barriers

- Stigma around mental illness

- Access to appropriate support systems and networks

- Education for the general population to increase knowledge and awareness of PTS

- Diversity in health care and mental health care is needed for optimally targeted support

Indigenous perspectives

There are gaps in knowledge and needs that are unique to First Nations, Métis and Inuit Peoples. Distinctions-based approaches are essential to best serve individual communities.

Following presentations and discussions with more than 20 Indigenous participants and First Nations, Métis and Inuit Elders, the following themes were identified.

Defining PTS within the Indigenous Reality

- Traumatic stress is ongoing: Many Indigenous communities continue to suffer from intergenerational trauma, abuse, substance use-related harms, suicide, racism and ongoing colonialism.

- Language is important: The language used to define PTS does not necessarily reflect the Indigenous reality. Indigenous words and phrases are needed to appropriately define PTS for Indigenous Peoples, and furthermore, the loss of Indigenous languages is a key contributor to PTS in these communities.

- Land-based system: Indigenous ways are centred around the land, and the loss of that land and related environmental issues are key factors contributing to PTS in Indigenous Peoples.

Developing an Indigenous Knowledge Research Framework: Ethical Space

Relationship building is critical to engage Elders and to establish an ethical space – an approach focused on openness and mutual learning – where Indigenous and Western knowledge systems meet. Research with Indigenous communities must be collaborative and based on reciprocity, respect, and the bidirectional sharing of knowledge. Truth and reconciliation also need to be front of mind when engaging Indigenous communities in the research process.

Indigenous Ways of Knowing: We Have Much to Learn

Indigenous ways of knowing and healing have demonstrated strength and efficacy and should be supported. Wellness approaches that are strength-based, land-based, focused on healing and wellness and that incorporate traditional practices unique to individual communities are the most effective.

Holistic Approaches to Wellness

Approaches to wellness that consider the mind, body, soul and spirit together may be relevant and effective for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous individuals living with PTS.

Diagnosis

Obtaining a diagnosis of PTSD or a PTS-related illness is rarely a simple, straightforward experience for many individuals. This section summarizes the identified barriers and potential facilitators to diagnosis, as shared by PWLE and mental healthcare providers.

Diagnosis is not the Beginning

- Stigma represents a major barrier for individuals to seek help for PTS. This may be community-based or broad, as mental illness is stigmatized to varying degrees within specific groups as well as generally across the country.

- Variability among symptoms, cultures, languages and experiences presents a challenge for timely, accurate diagnosis. Screening and diagnosis may take longer for certain individuals, for example, Indigenous Peoples or refugees. Tailored screening that takes into consideration a wide variety of symptoms as well as cultural factors and individuals’ unique experiences is needed.

- Primary care screening may be an effective tool in recognizing PTS, particularly in children. This could be accomplished by training primary care physicians on trauma-informed screening tools and how to respond effectively (e.g., reporting requirements for suspected abuse or neglect), for example as part of regular checkups such as well-child visits.

Education and Resources

- Community education may improve the general public’s understanding and awareness of PTS, which could help direct more people to seek assistance. It is important to raise awareness of the fact that PTS is not limited to those in specific professions such as military or PSP and can occur in any individual exposed to a trauma. PTS can occur regardless of sex or gender, age, ethnicity and other factors. Fostering culturally appropriate awareness of PTS and its symptoms may facilitate diagnoses within diverse communities.

- Often the patient is the sole focus of structured supports in medical care and the role families and loved ones play in diagnosis, treatment and recovery is ignored. Those providing support need evidence-based education and resources for supporting their loved ones.

Trauma-Informed Medicine

- Trauma-informed care may facilitate PTS diagnosis. Trauma is common, and therefore by recognizing that every patient may have experienced trauma, medical professionals may be better positioned to both diagnose PTS and to provide the best type of support and care.

- Continuity of care between therapists and physicians is important to avoid retraumatizing individuals living with PTS. Linking medical records and improving communication between healthcare providers could prevent individuals living with PTS from continually re-living their trauma.

Treatment

Treatment approaches for PTS-related illnesses should not be one-size-fits-all. In this section, PWLE identified several key factors to consider with respect to treatment for PTS.

Holistic, Wellness-Focused, and Trauma-Informed Care

- Holistic, whole-self approaches to treatment that consider physical, spiritual and mental health, as well as community and context, should be applied when treating individuals living with PTS. In particular, primary care and specialist physicians should be mindful of the potential need to address mental health concerns among those with chronic illness.

- Treatments should be personalized and malleable. This includes taking into consideration cultural and geographic diversity, as well as sex and gender, age and past experiences. Treatments should permit a shift in methods as needed to best support the individual and should consider alternative approaches, including Indigenous and other practices, where applicable.

Peer-to-Peer Support

- Peer-to-peer support throughout recovery can be an effective complement to standard medical care. Peer-based interventions, delivered by a trained peer support member, may be an effective way to increase access to treatment; however, more evidence on efficacy and feasibility of peer-delivered treatment is needed.

Barriers

- Access to culturally appropriate, evidence-based, trauma-informed treatment is needed. This includes improving access to both in-person and internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy (iCBT) and addressing the inequity in access to mental health care in Canada.

- Access to care without a PTS diagnosis is important for individuals who may not meet all criteria for PTSD but who nevertheless have reduced quality of life and need treatment. This gap may be especially evident in Indigenous and racialized populations.

- For Indigenous communities, one of the biggest barriers noted during discussion was the neglect of Indigenous healing practices within the Western definition of evidence-based care.

Summary of Workshop Sessions

Support

Lack of social support has been cited as one of the major risk factors for the development of PTSD. Although diverse support systems exist, knowledge gaps remain surrounding access, and what types of support are most effective, and for whom. It is also important to maintain a balance of supports that are effective for each individual, while ensuring support does not replace health care.

Peer-to-Peer Support

Peer-to-peer support stood out as a valuable contributor to the overall wellness of individuals living with PTS, but the field needs additional research and resources. Peer Support Canada defines peer support as the “… emotional and practical support between two people who share a common experience, such as a mental health challenge or illness.” Peers understand an individual’s unique perspectives and stressors, in some cases better than family or friends. Though peer support is relevant to all individuals living with PTS, it was particularly emphasized with respect to unique experiences such as individuals with a specific disease, or PSP. Networks of patients or people with lived experience of chronic illness may be valuable to support mental health.

Access to quality peer-to-peer support can be challenging. Stigma, which can include self-stigma or community stigma, is a significant barrier. Self-stigma is the incorporation of negative beliefs or prejudices about mental illness into thoughts and actions towards oneself. Additionally, a lack of public awareness of PTS may hinder effective peer-to-peer support. Often, there is a misunderstanding within the community of who is vulnerable to PTS. There is a continued misconception that only individuals who have experienced combat situations or workplace operational stress injury (e.g., police work) are vulnerable to developing PTS. For example, it may not be well understood that individuals with a chronic illness such as multiple sclerosis or cancer may experience PTS, making it difficult to identify support networks. Workplace stigma within public safety and veteran populations can also decrease help seeking for mental health concerns.

Internet-based peer support may be beneficial, particularly for individuals living in rural or remote locations, or for veterans returning home from overseas deployment. This type of support is easily accessible with an internet connection and allows individuals to connect with each other without geographic barriers. The anonymity of online communication may be both a benefit and a challenge. Individuals may feel more comfortable in an online space; however, it was noted that there is a risk of non-qualified individuals providing advice online. A system that could filter or moderate online peer-to-peer support is needed.

Support Networks

Individuals living with PTS often build their own formal and informal support networks consisting of families, friends, care providers and communities. These networks can facilitate peer-to-peer support opportunities, offer diverse connections to individuals and communities with similar experiences, and can be a much-needed resource for individuals who are supporting a person living with PTS.

Holistic, trauma-informed support for physical illness should be combined with support for mental and spiritual wellness. Trauma-informed care is an approach which focuses on reducing re-traumatization while understanding the medical sequelae of trauma. It is well established that chronic illness has a bidirectional relationship with many mental health challenges including depression, anxiety and PTS. However, these issues are often treated separately by different providers. In addition to illnesses such as cancer and multiple sclerosis, it was noted that there is a significant gap with respect to the mental health of organ recipient patients. Organ recipients may experience adverse emotional and mental health outcomes including worry, guilt, anxiety, and a feeling of responsibility to the donor and their family which can persist following organ transplant. Beyond physical healing, mental wellness and spiritual supports are needed as patients work through these difficult emotions.

“See all of me, treat all of me.”

Family members and caregivers of individuals with PTS may benefit from support networks that are specific to their needs. In addition to providing support to their loved one, these individuals are often navigating the healthcare system on someone else’s behalf and with limited information. Families and caregivers may also experience peripheral and vicarious trauma, as well as stress, isolation, depression and anxiety. Access to support networks dedicated to family members and caregivers of individuals with PTS can provide valuable connections to individuals with similar experiences and helpful expertise, while also providing a conduit for improving care for the individual living with PTS. Peer-to-peer support for families and caregivers can be a source for stigma reduction and logistical education for those providing direct and possibly daily support.

Community support networks may be effective to enhance community wellness and promote resiliency. Knowledge and acceptance are at the root of reintegration. Sharing knowledge and experiences at the community level can also help combat stigma. Community centres where people can gather and share stories may be particularly effective and are extremely important in Indigenous communities, immigrant and refugee communities, and rural/remote areas. Having a physical place to gather is important to facilitate the development of community support networks and overall well-being.

Support for Reintegration Following Trauma

Support for reintegration following trauma is important for individuals with PTS in order to ensure functional wellness and facilitate successful return to work, family life, and society. In professions where operational stress injuries are prevalent, (e.g., PSP and military) there are existing and evidence-based reintegration programs and processes; however, these may be insufficient or inappropriate beyond their intended communities.

Factors contributing to successful reintegration following trauma may include: desensitization to aversive stimuli through conventional therapy, peer-to-peer support, trauma-informed treatment, treatment for problematic substance use, and privacy and confidentiality.

The Critical Incident Reintegration Program developed for the Edmonton Police Service is a streamlined, peer-driven return-to-work program for police officers and other PSP. The program includes both short-term and long-term variants and is highly malleable. It may be modified to suit different industries, demographics and land, and has been applied successfully to Alberta RCMP and Edmonton Metro ECS. Some participants report success with the program, but there is a need for research to validate the process and look at long-term outcomes.

Barriers to Support

Several barriers to support were highlighted through group discussion, and using an interactive real-time online app.

Stigma remains a key barrier affecting individuals living with PTS, including self-stigma and community stigma. In populations with high rates of operational stress injury, ensuring privacy and confidentiality may make it more likely that an individual living with PTS will seek support. Stigma within these occupations, especially among individuals in leadership positions, can also be a barrier to seeking support.

Access to appropriate support systems and networks is a challenge. Since PTS can affect anyone, it is important that supports are tailored and targeted to the individual. Access to formal and structured support may be particularly difficult for Indigenous Peoples, individuals living in rural/remote areas, marginalized communities and youth.

Knowledge sharing to improve awareness of PTS within the general population is needed. This includes topics such as signs and symptoms to recognise PTS in a loved one and improve societal understanding of PTS. The language used to educate the public should be lay friendly, evidence-informed and come from an authoritative source. For Indigenous populations, trauma is not considered “post,” therefore the definition of PTS needs to also consider the Indigenous reality.

Structural injustice, including structural racism, sexism and unconscious bias are barriers to health care and mental health care. Health equity in geographic, cultural and economic diversity, as well as sex and gender, are important factors to consider with respect to support for individuals living with PTS. Additionally, there are gaps in support for Indigenous Peoples, including residential school survivors and their families, as well as incarcerated individuals and their families.

Indigenous Perspectives

More than 20 Indigenous participants contributed to this workshop, providing perspectives and highlighting knowledge gaps that uniquely apply to Indigenous Peoples. Four Indigenous Elders from First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities collaboratively led a half-day session dedicated to Indigenous perspectives of PTS. The session included stories from the Elders and discussion with all workshop participants. A summary of the knowledge gaps that were identified in this session are summarized below.

Defining PTS within the Indigenous Reality

Traumatic stress remains an ongoing, daily reality for Indigenous communities. As said by one participant and echoed by others at the workshop: “it is not ‘post’ traumatic stress” – and this distinction must be taken into account when considering Indigenous wellness. Ongoing colonialism, racism (including systemic racism), intergenerational trauma, increased rates of suicide, victimization, and problematic substance use are significant challenges for Indigenous Peoples. In addition, the impacts of residential schools are still being felt by Indigenous communities. Breaking the cycle of trauma is desperately needed.

Clinical language used to define and diagnose PTS does not reflect Indigenous reality, or views about trauma and mental wellness. A definition of PTS that uses Indigenous word(s) and conceptualization of mental wellness is needed.

Colonialism and the loss of Indigenous languages are key contributors to PTS in Indigenous Peoples. The loss of language represents the loss of connection to ancestors.

Indigenous ways are grounded in a land-based system and therefore the loss of land and environmental issues are key factors contributing to PTS in Indigenous Peoples.

Developing an Indigenous Knowledge Research Framework: Ethical Space

Colonial approaches to research have led to a mistrust of research and researchers within Indigenous communities. There is a history of researchers entering Indigenous communities, doing research on the people, and not with the people. This has led to the word research having a negative connotation. Furthermore, knowledge gained through research is routinely not shared with the communities, demonstrating a lack of respect, reciprocity and collaboration.

Ethical space is the concept of working and developing a safe space between two knowledge systems and cultures, which may have disparate views. This ethical space is rooted in dialogue and requires relationship and trust building. Elders are valuable allies and keepers of knowledge, and they may be willing to guide researchers to work with communities. Elders can also act as a liaison between their communities and researchers, helping to facilitate the ethical and respectful navigation of cultural sensitivities and language barriers.

Figure Legend: A graphical representation of an Indigenous Knowledge Research Framework, an approach to creating an ethical space to discuss research with Indigenous communities.

Long description

Indigenous Ways of Knowing

Commitment

Acceptance

Awareness

Reality

Going forward, it is important to approach all research with Indigenous communities with truth and reconciliation at the front of mind. With this approach, research must take the time to establish relationships built on mutual respect and understanding, and to create an ethical space between Indigenous and Western knowledge systems. Researchers from outside an Indigenous community must also consider how they may be seen to have power over a community. This ethical space must be built together with each community and research team as a space that no one owns, where engagement involves openness and mutual learning. This ethical space may evolve over time and with each research scenario.

Indigenous Ways of Knowing: We Have Much to Learn

Approaches to wellness that are most effective for Indigenous communities are strength-based and focused on healing and wellness. Land-based therapies and practices focused on storytelling, connections to Elders, and relationship building are valued and effective in Indigenous populations.

There is tremendous strength in Indigenous ways of knowing and demonstrated efficacy in Indigenous approaches to wellness. Indigenous ways are often not respected within Western approaches to mental health. There is a need for more Indigenous-led research to explore where Western approaches and Indigenous knowledge could be complementary or adapted. A dialog between Indigenous youth, Elders, and the research system can set a path of mutual respect for the future.

There is variability between communities, and local traditions and practices should be explored and supported. Specific examples highlighted included: smudging, drum circles, feasts, vision quests and sweat lodges, as well as gathering/storytelling.

Holistic Approaches to Wellness

Approaches to wellness that are person-centred and focused on the mind-body connection were highlighted throughout the workshop. Importantly, approaches that consider the mind, body, soul and spirit together, are central to Indigenous healing and wellness.

Diagnosis

Obtaining a diagnosis of PTSD or a PTS-related illness is rarely a simple, straightforward experience. This section summarizes the identified barriers and potential facilitators to diagnosis, as shared by PWLE and mental healthcare providers.

Diagnosis is not the Beginning

The pathway to diagnosis begins when an individual first recognizes problematic symptoms, often well before they seek help from a physician. The journey to seeking care can vary depending on the support system and barriers each individual encounters.

Often, stigmapresents a major barrier to seek help for PTS. Mental illness is still stigmatized across the country, with variability across communities and professions. Self-stigma and community-based stigma impact care seeking and the ability to identify signs and symptoms of PTS in oneself and others. In addition, some individuals may have increased stigma due to the type of trauma they have endured. For example, victims of sexual assault may have additional stigma to overcome. Normalization of mental illness, and community education about the causes and populations who are most vulnerable to PTS may increase access to care.

Variability in symptoms across cultures and languages presents a challenge for timely, accurate diagnosis. For some, the clinical language used to describe and diagnose PTS may be insufficient. This can prolong the screening and diagnosis process for certain individuals, for example, Indigenous Peoples or refugees. Tailored screening that takes into consideration a wide variety of symptoms and cultural factors is needed.

Special consideration needs to be given to children and youth who have been or are currently victimized. Care seeking can be particularly problematic for children who are unable to request help without facing repercussions in their home environment. For those under 18, treatment will often not be delivered without parental consent. Primary care screening may be an effective tool in recognizing PTS, particularly in children. This could be accomplished by training primary care physicians to screen for PTS symptoms as part of well-child visits.

Education and Resources

Support structures such as friends, family or coworkers can be helpful resources for individuals seeking or receiving treatment.

Better community education about the causes and symptoms of PTS can reduce stigma within the community. Across Canada, there is a common misconception that only individuals who experience combat or frontline work (e.g., police, fire services, etc.) are at risk of developing PTS. Community education may therefore improve the general public’s understanding and awareness of PTS, which could help direct more people to seek assistance. This education should also incorporate culturally relevant language and contexts in order to facilitate PTS diagnoses in diverse communities.

Family resources are needed to support families through the diagnosis and treatment of a loved one. Diagnosis can impact the family and relationships. Often, the sole focus of structured supports in medical care focus on the individual with PTS, and ignore the role families play in diagnosis, access to care, treatment and lifelong supports. Increased attention is needed to provide families with evidence-based education and resources for supporting loved ones in need.

Trauma-Informed Medicine

Trauma-informed care may facilitate PTS diagnosis. Trauma is common, and therefore by recognizing that every patient may have experienced trauma, medical professionals may be better positioned to diagnose PTS and provide the best support and care. Increased awareness of the physical symptoms of PTS, and how people present to their physicians is needed. Often, people will readily discuss stress, sleep difficulties and gastrointestinal issues without recognizing there is an underlying mental health issue. Formal support networkssuch as medical providers, therapists and other care support are important in providing a framework for care to individuals with PTS. These formalized support networks may also have a greater role in wellness for those with a chronic illness.

Continuity of care between therapists and physicians is important to avoid retraumatizing individuals living with PTS. Through the process of diagnosis, an individual seeking treatment will often be asked to recount their trauma, history and symptoms to primary care physicians, medical specialists, therapists and social workers. Linking medical records and improving communication between healthcare providers would prevent individuals living with PTS from having to continually relive their trauma. There is a need for improved continuity of care across the lifespan.

Transitions in care from pediatric to adult services are difficult for those who received care as a child. For young people with chronic illnesses who require long-term specialist health care, the burden of information is often placed on the young person to acclimate and bring their new medical team up to speed. Information is often lost in translation, causing treatment gaps.

Treatment

Despite having many clinical tools available to treat PTS, evidence-based treatments are only effective for about half of individuals seeking care. This treatment gap even wider for those with structural barriers to care such as language, culture or financial limitations.

Holistic, Wellness-Focused, and Trauma-Informed Care

In the general Canadian population, it is estimated that more than 75 per cent of adults have been exposed to at least one event that would be enough to cause PTSD. Trauma-informed care is a method that incorporates a compassionate approach to the physical and mental health needs of trauma survivors. An overall shift to trauma-informed care is needed across the medical system. Considering the high prevalence of trauma within the general population, this approach could improve medical and mental health care for many Canadians.

Adapting medical approaches towards holistic care was a theme across all sessions. In addition, a shift towards a collaborative dialogue with medical care providers was seen as an urgent need towards improving treatment outcomes.

Individualized treatment plans should consider culture, community and the context of the trauma. This includes taking into consideration cultural and geographic diversity, as well as sex and gender, age and past experiences. In addition, clinicians need to consider and provide treatment plans that are aimed at addressing the goals of the patient across the mind, body and spirit.

“We are taught that the wounds of the soul are not as important as the wounds of the body.”

Treatments should permit a shift in methods as needed to best support the individual’s health, and should consider alternative approaches as applicable, including Indigenous and other practices. While many people will see improvements from Western medicine, special consideration needs to be given to individuals who are not improving or have continued poor quality of life. Health care approaches that include practices outside of Western medicine may be an effective option for those who have experienced multiple treatment failures. Increased diversity within healthcare professions may also improve access to culturally relevant treatment approaches.

There is a need for tailored and personalized care. From a cultural perspective, this includes increasing awareness of cultural variances in symptom description and presentation. A focus on wellness and strength-based treatment, rather than illness-based frameworks, may be more relevant within Indigenous communities. Furthermore, all individuals living with PTS may be empowered by treatments that focus on acknowledging their strengths, building resiliency and emphasizing wellness over illness.

Peer-to-Peer

Peer-to-peer resources are often a starting place for treatment seeking, and a forum for support through treatment. Peer-to-peer support during treatment is often individualized assistance that is developed collaboratively and is not prescriptive. This type of support can be an effective complement to standard medical care and may increase quality of life outcomes through dialogues on shared experience and treatments (e.g., medication types, talk therapy treatment types, spiritual support, etc.). Peer-based interventions delivered by a trained peer-support member also exist, but more research is needed to determine best practices and efficacy.

Barriers

Access to care is a top concern for individuals living with PTS. With increased time pressure during family physician visits, screening for mental wellness may not be prioritized. Additional accessibility issues include financial constraints, knowledge of navigating the medical system, and stigma. In addition, lacking a formal diagnosis of PTSD can be an extraordinary barrier to receiving treatment. Provincial healthcare treatment options, or insurance coverage may not be available to individuals who do not have a formal diagnosis. This particular gap in diagnosis may be especially evident in Indigenous and racialized populations.

Improving access to both in-person and internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy (iCBT) is important to addressing the inequity in access to mental health care in Canada. Increasing the number of social workers and healthcare navigators within the medical system could also help address some of the inequities in mental health care access.

For Indigenous communities, the lack of recognition of Indigenous healing practices is a major barrier. The Western definition of evidence-based care does not include Indigenous healing and knowledge, despite the fact that there is evidence to support these treatments. These healing practices continue and are based on centuries-old traditions; however, accessing this type of care in collaboration with traditional medicine remains a barrier.

Beyond traditional healing, increased access to culturally appropriate and adapted treatment is needed. Increased efforts should be made to expand culturally adapted trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and cognitive processing therapy (CPT) to address needs of a diverse Canadian population.

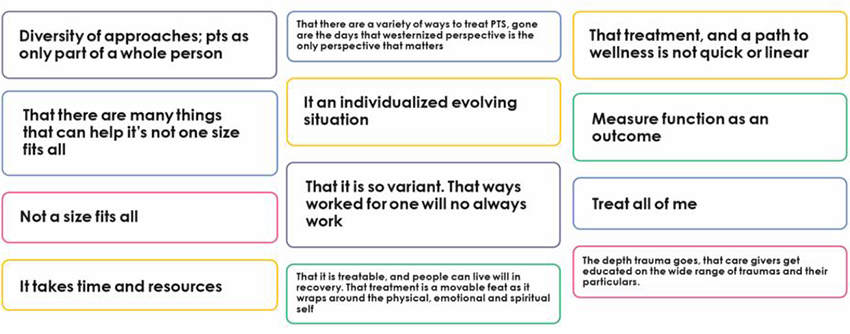

Figure Legend: Responses to: What is something you wish everyone knew about the treatment of PTS?

Long description

Responses to: What is something you wish everyone knew about the treatment of PTS?

Diversity of approaches; PTS as only a part of the whole person.

That there are many things that can help; it’s not one size fits all.

Not a size fits all.

It takes time and resources.

That there are a variety of ways to treat PTS, gone are the days that a Westernized perspective is the only perspective that matters.

It is an individualized, evolving situation.

That it is so variant. That what worked for one will not always work.

That it is treatable, and people can live well in recovery. That treatment is a moveable feast as it wraps around the physical, emotional and spiritual self.

That treatment, and a path to wellness, is not quick or linear.

Measure function as an outcome.

Treat all of me.

The depth trauma goes, that caregivers get educated on the wide range of traumas and their particulars.

Contact us

University of Calgary

Cumming School of Medicine

Heritage Medical Research Building, Room 172

3330 Hospital Drive NW

Calgary, AB T2N 4N1

403-210-7161

INMHA-INSMT@cihr-irsc.gc.ca

- Date modified: