COVID-19

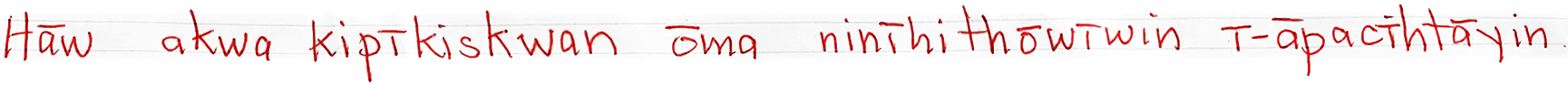

Now you’re speaking my language!

COVID-19 risk communications for First Nations people by First Nations people

The Rapid Response call for applications was a brilliant idea, as the competition and funding cycle took weeks instead of months. Rather than being restricted to doing a post-crisis audit of what worked and didn’t, this funding now allows us as researchers and advocates to be on the frontlines, actively playing whatever support role we can alongside communities and regional tribal organizations as they adapt and respond to this virus.

This research has confirmed existing inequities in First Nation communities, but it has also demonstrated First Nations’ people’s resilience and their ability to develop countermeasures in the face of COVID-19.

This project represents an opportunity to learn about ways pandemics and other health emergencies have impacted First Nations communities. The research will also provide critical insight into ways they are coping with and responding to them.

The COVID-19 pandemic may be dominating the headlines in mainstream media, but it would be unwise to assume that messages about infection risks and public health measures are reaching all audiences equally.

During the H1N1 crisis, for example, Indigenous communities in Canada often lacked access to medical experts and relevant health information—which contributed to misinformation and fear that can still be felt a decade later.

Yet, many Indigenous communities and organizations responded effectively to reduce the worst impacts of the outbreak, although their efforts were largely undocumented. This shows that there is much to learn from these past experiences. Putting those lessons to use during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic provides an opportunity to build on past successes, and from public health responses rooted in community priorities.

Kitatipithitamak mithwayawin, Cree for “we have ownership and sovereignty over health,” is a multi-centre research project that has been designed to do just that. It brings together First Nation and allied scholars, community leaders and Elders, with health agencies and Indigenous political organizations to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic in a strategic and culturally appropriate way.

The project is co-led by Dr. Stephane McLachlan, Professor with the Department of Environment and Geography at the University of Manitoba; Dr. Myrle Ballard, Assistant Professor in Chemistry and Indigenous Scholar at the University of Manitoba and member of the Lake St. Martin First Nation; and, Dr. Ramona Neckoway, Assistant Professor in the Department of Aboriginal and Northern Studies at the University College of the.North, and a member of the Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation.

The project team members are determined to save lives in a way that underscores the effectiveness of Indigenous cultures and traditions and acknowledges the richness of Traditional Knowledge when it comes to informing COVID-19 countermeasures.

Learning from past mistakes to create a better future

Historically, infectious diseases have exacted a disproportionately heavy toll on Indigenous communities. With the influx of European settlers to Canada came the introduction of pathogens that Indigenous Peoples lacked exposure to, meaning their immune systems were unprepared to mount the biological defenses necessary to withstand these deadly infections.

The health and well-being of Indigenous Peoples suffered dramatically from diseases including smallpox, tuberculosis, and Spanish Flu, which caused large-scale disruption of traditional lifestyles, livelihoods, and cultural practices. Vibrant Indigenous communities were decimated as a dark chapter in Canadian history unfolded.

In the decades since, Indigenous Peoples have grappled with successive waves of challenges, displaying incredible resilience in the face of adversity. The encroachment of industry and settlement has led to a loss of habitat for game and fish stocks and the contamination of traditional country foods. Residential Schools and the Sixties Scoop caused a rupture in the transmission of Traditional Knowledge from one generation to another. These factors converge to negatively impact food security, forcing Indigenous Peoples to become increasingly reliant on expensive and nutritionally deficient store-bought foods.

Today, the geographic reality of many Indigenous Peoples impose yet another challenge, as access to modern health care facilities remains far from universal. A chronic lack of clean drinking water in many Indigenous communities across Canada also impedes their ability to adopt the most basic public health practices. Compounding the problem is inadequate housing and community infrastructure e.g., road access, waterworks, utilities, internet, etc.

Self-isolation and social distancing in a pandemic is next to impossible as the number of housing units in many communities fails to address the needs of Indigenous Peoples, the youngest and fastest growing segment of the Canadian population.

For these reasons and more, it is imperative to be mindful of the impacts of COVID-19 on Indigenous communities and to affirm the importance of culturally safe, relevant, and co-created tools when reducing its spread.

At the intersection of traditional and western knowledge

Drs. Ballard, Neckoway, and McLachlan are striving to be part of the solution working toward a brighter future through their research project, which focuses on Indigenous-led countermeasures to COVID-19 and past pandemics. It serves as a tangible example of the power of collaboration and knowledge sharing when it comes to health and wellbeing.

Anchored in the strengths of Indigenous Peoples’ health systems, inextricably linked to the overall health of the ecosystem, the outreach and support campaign addresses the importance of physical and spiritual health holistically, incorporating western science (where appropriate) but remaining grounded in Indigenous knowledge, traditions, and even humour.

Their creative initiatives to share crucial information about COVID-19 use a full-circle approach—that is, community-led initiatives directed to Indigenous community members.

The same rich oral tradition that still permeates every aspect of Indigenous Peoples’ daily life is the team’s secret sauce.

In a short amount of time, the project has taken off, netting an impressively large audience (15,000+) dispersed over thousands of kilometres via a targeted social media campaign that features videos in Cree with English subtitling and has garnered media attention from around the world. To produce the videos, the researchers collaborated with puppeteer Samson Hunter, creator of “Kahkakiw, a Raven from Northern Manitoba,” as well as Elders and long-time educators, Phyllis and Donald Hart, all of whom are also from Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation.

Building on its popularity in Cree pop culture, Kahkakiw, (pronounced Ka-Ka-Cue. ᑲᐦᑲᑭᐤ), conveys disease-prevention precautions in a dynamic and playful way, becoming an amplifying voice for public health agencies and community health experts hoping to share relevant advice about COVID-19 with an Indigenous audience.

To date, there are three “Kahkakiw, Straight Talk About Coronavirus” videos in the series with more in the works. The first focuses on introducing COVID-19, the second on social distancing and the last, on children. To reach a younger audience, companion resources for children, including educational colouring pages and puzzles that share relevant health and cultural information are also being rolled out. In addition, Indigenous community members are encouraged to share with others their day-to-day realities during the COVID-19 pandemic on a dedicated social media page and related project website. These shared experiences go a long way to relieving anxiety and provide an excellent forum for the exchange of information.

The popularity of the videos and the uptake of the social media resources are showing early signs of success for the kitatipithitamak mithwayawin project, and serves as a powerful reminder of the need to develop culturally appropriate community-based public health messages and programs.

- Date modified: