Our face holds the key to diagnosing rare genetic conditions—and 3D facial imaging could make it possible

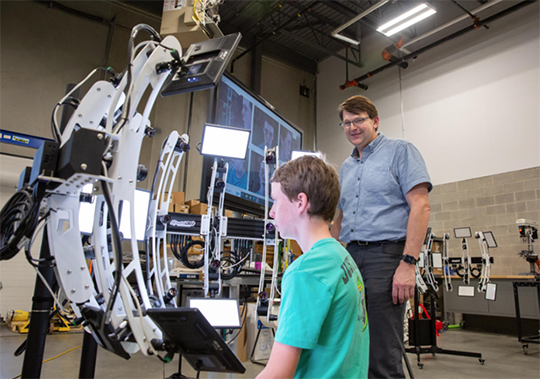

A young patient sits calmly as several 3D cameras scan his face. In seconds, a computer analyzes his facial features while quickly sifting and comparing through a large dataset of facial images. A heat map glows on the screen, showing areas in the face affected by a rare genetic condition. It may sound futuristic but it’s happening right now at Dr. Benedikt Hallgrimsson’s lab at the University of Calgary.

“It is extraordinary that the shape of the face would predict inherited connective tissues diseases that have nothing to do with the face,” says Dr. Hallgrimsson. Rare genetic mutations that affect connective tissues can also alter facial features—a connection his research is helping to uncover.

Inherited connective tissue diseases such as Marfan syndrome, Loeys-Dietz syndrome, and osteogenesis imperfecta often require complex care beginning in the first years of life, but according to Dr. Jida El Hajjar, the Executive Director of the Loeys-Dietz Syndrome Foundation Canada, many of these conditions can go undetected for years:

“Families affected by rare genetic conditions such as Loeys-Dietz often describe a long and exhausting diagnostic journey,” she explains. “Multiple visits to doctors and specialists and a lot of patient advocacy place an unnecessary emotional burden on patients and caregivers and contribute to delayed or missed diagnoses.”

But Dr. Hallgrimsson’s promising 3D imaging technology could change that, helping doctors provide a faster diagnosis and, ultimately, improved patient health.

Dr. Hallgrimsson’s long research journey has involved researchers from around the globe. They first developed a large dataset of facial shapes from participants from diverse ethnic backgrounds who live with several rare genetic conditions.

With funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and National Research Council, Dr. Hallgrimsson’s team then designed a computer model powered by machine learning. It can classify facial patterns in the dataset and search for distinguishing features affecting the whole facial shape or specific facial parts.

But bringing the model into clinical practice wasn’t easy. The original 3D imaging technology required bulky, sophisticated cameras which were not exactly ideal for a small medical clinic. Furthermore, babies and young children struggled to stay still enough for scans, making it difficult to capture high-quality images.

Dr. Hallgrimsson found the solution by pure chance. He was lining up at the security line at the airport, when he met Ira Laughy, founder of Rapid 3D, a local engineering company. This chance meeting sparked a university-business collaboration to build a powerful and yet compact 3D machine suitable for clinical use.

Although researchers are continuing to refine the tool’s accuracy to account, for instance, for facial differences across ethnicities, its potential is already clear. “It could be used as an early diagnostic tool in primary care and pediatric clinics, where health care providers may not be trained to recognize congenital alterations,” says Dr. Hallgrimsson. The tool would help flag patients for further testing and even inform a preliminary diagnosis when genetic tests come back inconclusive, which is 40% of cases.

“The research led by Dr. Hallgrímsson has the potential to reduce diagnostic delays, ease the advocacy burden placed on families, and support more timely care for people living with some rare genetic conditions” adds Dr. El Hajjar whose foundation is collaborating with Dr. Hallgrimsson.

With new CIHR funding, the team is now exploring an exciting clinical application for 3D facial imaging: the tool would help doctors determine the severity of heritable thoracic aortopathies—genetic conditions affecting connective tissues and cardiovascular health. It would also guide treatment options, such as targeted medications and frequency of follow-ups.

“Physicians and patients make these decisions together,” explains Dr. Hallgrimsson. “So the more information we can provide them, the better.”

At a glance

Issue

Inherited connective tissue diseases such as Marfan syndrome, Loeys-Dietz syndrome, and osteogenesis imperfecta often require complex care, but these genetic conditions can go undetected for years, delaying much-needed care for young patients.

Research

Dr. Hallgrimsson’s 3D facial imaging tool promises to detect these conditions early. In collaboration with a local 3D company and the Loeys-Dietz Syndrome Foundation Canada, Dr. Hallgrimsson’s team is now working to help doctors not just diagnose but also guide treatment options for patients. This research on genetic disease diagnosis is a significant component of the One Child Every Child research initiative, which is supported by the Canada First Research Excellence Fund.

To learn more, watch the video about this research project.

- Date modified: