'Breath-giving' research efforts could lead to more effective lung transplants

Two CIHR-funded researchers in Toronto are analyzing how lungs function outside of the human body

People breathe in and out approximately 22,000 times per day. But if they have trouble breathing regularly and experience difficulties moving as a result, patients may need something more than antibiotics or an inhaler as treatments – they may need a donated set of lungs.

The world's first successful lung transplant took place in 1983 at the Toronto General Hospital. In Canada, lung transplants have since expanded from Toronto to medical facilities in Vancouver, Edmonton, and Montreal. The number of recipients has also increased to 361 in 2020. While this is significant progress, in 2018, 270 people were on a waiting list for a donation of lungs - and 28 people died as a result.

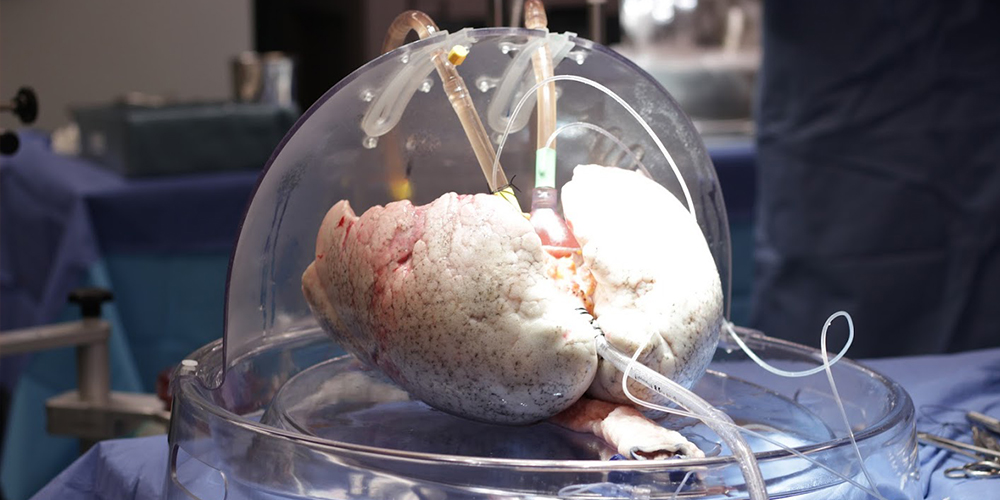

Fortunately, Dr. Marcelo Cypel and Dr. Ana Andreazza are conducting CIHR-funded research that benefits recipients in various ways. The team is storing donated lungs differently so that they can be preserved for much longer after they've been removed from the donor, which may increase the availability of the organ for transplantation. By sustaining the lungs in a protective dome with oxygen and basic nutrients, Dr. Cypel and Dr. Andreazza are also analyzing why the organ sometimes fails after the transplant takes place.

At a glance

Issue

Although 361 successful lung transplants took place in Canada in 2020, even more could occur if all donated lungs were used due to advanced strategies to preserve and treat the organ.

Impact

Researchers and surgeons in Toronto discovered that mitochondria help preserve lungs for 36 hours if they're stored at 10°C. Because mitochondria create energy from oxygen in cells better at that temperature, CIHR-funded researchers are now examining whether injections of this genetic structure can repair damaged donated lungs that are sustained with oxygen and nutrients outside of the body in a protective dome-machine at 37°C.

Results

If this proves to be successful, more patients will have access to lung transplants. Recipients may also live longer after the transplant because they've received donated lungs that are in a better state.

Related stories

Improving the new beginning for patients

It used to be that surgeons had only between 6-8 hours to transplant lungs from donors into recipients because the organ had to be clinically stored on ice at 4°C.

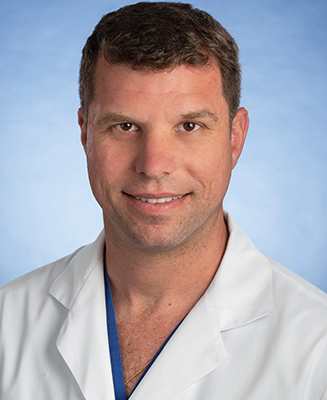

By storing up to two sets of lungs at 10°C in an incubator, Dr. Cypel, who is Surgical Director at Ajmera Transplant Centre at University Health Network (UHN) and a Canada Research Chair in Lung Transplantation, has discovered that mitochondria can protect the organ for up to 36 hours instead.

As Scientific Director of the Mitochondrial Innovation Initiative at the University of Toronto and the Thomas C. Zachos Chair in Mitochondrial Research, Dr. Andreazza is helping Dr. Cypel further examine the benefits of this discovery.

"When you breathe, mitochondria are important because they absorb oxygen and produce energy that helps keep cells that they inhabit alive," said Dr. Andreazza. "For this study, Marcelo's team sends me tissue samples from donated lungs so that I can analyze whether the mitochondria still have life after eight hours. If the answer is 'yes', we can put them in a solution that stabilizes things for a possible transplant."

Mitochondria are genetically passed along from mothers to their children. The question remains whether a transplantation of mitochondria between two patients who are not related can be effective.

"Our three research goals are to increase the allotted time of organ preservation, improve the quality of donor organs so we can transplant more of them, and create better patient outcomes by decreasing early injuries to the lungs after they've been transplanted," said Dr. Cypel.

"At 4°C, the mitochondria slow down and shut down the respiration," said Dr. Andreazza. "By changing the temperature to 10°C, the mitochondria aren't inert anymore and maintain metabolism in cells. It makes a lot of sense for us to investigate whether this could maintain better outcomes for the patients."

"We may be able to protect the mitochondria up to a certain point," said Dr. Cypel. "But lungs have already experienced injured mitochondria due to other reasons, such as inflammation, mechanical ventilation problems, or pneumonia. If we could possibly transplant healthy mitochondria to these lungs, would their metabolism help preserve the organ for a longer period afterwards?"

Answers to this research question will be determined when new and healthy mitochondria are inserted into damaged lungs that are sustained ex vivo (out of body) in a protective dome-like machine that provides oxygen and nutrients to the organ, and maintains a normal body temperature of 37°C.

Patients praise these breath-giving research efforts

As it stands, patients have a 60% chance of surviving up to six years after they've received lung transplants from a donor. This is because lungs are one of the only organs that are constantly exposed to the external environment and possible bacterial infection, leading to higher rates of rejection.

Still, Eric Celentano remained optimistic. In 2018, Dr. Cypel transplanted donated lungs into him at UHN. Ironically, prior to his diagnosis in 2013 with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, a progressive scarring disease that reduces lung capacity, Mr. Celentano was a sales specialist of respiratory therapy equipment with Summit Technologies for 25 years in Vancouver. At age 65, he's still grateful that he received another chance at life thanks to UHN – even if he got called for it twice.

"The first time Dr. Cypel and his team prepped me for a lung transplant surgery at UHN, they tested and treated the organ ex vivo in the pod for about six hours before they determined that it wasn't suitable for me," said Mr. Celentano. "They sent me home as a result. I'm so very happy that they were that diligent. When I got called to the hospital a second time for a lung transplant, I was prepped for surgery and waited six or seven hours while they screened the organ and determined everything would be OK to go through with the operation."

After the lung transplant, Mr. Celentano had to go through 16 days of recovery before he was discharged from the hospital. Then he underwent three months of physiotherapy. Fortunately, he had family members in Toronto – and was able to recover with his sister by his side 24 hours per day over a period of three weeks. Since then, he's helped new patients understand that they should always listen to their doctors by taking medication after the transplant so that their new lungs will not be rejected by their body, and that they should incorporate exercise into their daily routine.

"I use a treadmill and lift weights in a fitness centre at my condo, and I also take frequent walks outside and play golf," said Mr. Celentano. "As a retiree, I have time to talk about the value of lung transplants to healthcare workers so that they can learn about efforts being made to help recipients survive the process by listening to their perspectives. I'm also involved in a patient support group for those who suffer from pulmonary fibrosis, I'm a Patient Advocate for organ donation at Trillium Gift of Life in Ontario, and I'm a member of the Toronto Lung Transplant Civitan Club, which raises funds for patients who have move to Toronto and wait for a lung donation."

Hélène Campbell is another patient who, like Eric, needed a new set of lungs. While she was diagnosed with asthma, she thought it could be something more severe because she was consistently short of breath. After months of medical speculation, a respirologist in Ottawa diagnosed that she urgently needed to receive a double lung transplant.

"It didn't make sense, but at the age of 20 I had idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, which is commonly found in a person who's 60-years-old or older," said Ms. Campbell.

She and her mother, a registered nurse, moved to Toronto to wait for a pair of lungs that would be a suitable match at UHN. This had a psychological impact on Ms. Campbell because she was separated from the rest of her family in Ottawa, she had to use money set aside for her education to pay for her accommodation, she was perpetually on oxygen, and she needed to learn about the transplant itself. But she kept optimism through hope.

"I wouldn't be here right now if it wasn't for Dr. Cypel's innovative ex vivo machine," said Ms. Campbell. "Before the transplant, the UHN surgeons had to cut out lobes of a donated set of lungs in that machine because, while they were compatible with my body, they were too big to fit in my chest."

Ms. Campbell was down to a 6% breathing capacity when she received these new lungs in April 2012. After recovery, she promoted the need for people to donate lungs through use of social media, interviews, and speeches. While Ms. Campbell's body ultimately rejected her new lungs, she was fortunate to get another set of lungs donated at UHN in September 2017. After her second recovery, she received a key the City of Ottawa and had a street named after her in recognition of her efforts to promote organ donation.

Ms. Campbell loves the UHN team and admires Dr. Cypel's and Dr. Andreazza's collaborative research efforts to make things better for future recipients.

"It's so exciting!" she says. "It's encouraging to know that their progressive research into mitochondria is trying to make transplants more effective thanks to the strength of the donors' lungs. It's clear that they're both passionate about this, and they care so much."

As a patient partner lead with Health Standards Organization, Ms. Campbell now works with experts and people with lived experience to develop standards, assessment programs and quality that will improve health services around the world.

"It's so rewarding to be part of this partnership, because I know that I'm helping improve the health of others in the future," she says. "To me, that's all that matters."

- Date modified: