Integrating Ethics and the Knowledge-To-Action Cycle

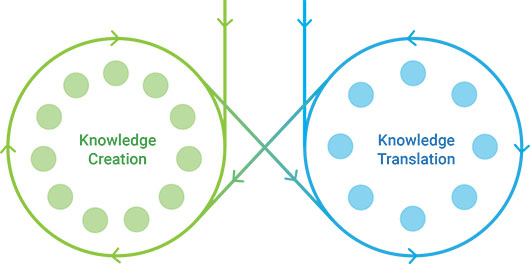

This section presents the KTA–E cycle. As a conceptual framework, this cycle illustrates the iterative relationship between knowledge creation and knowledge translation and some of the potential ethical considerations at steps along the way. It builds on the work of Graham et al., 2006 Footnote 1. The framework addresses the complete lifecycle of scientific knowledge relevant to researchers funded by CIHR and includes a wide variety of elements from data collection to sustaining knowledge use. All of the materials presented in this Workbook are informed by, and map onto, this conceptual framework.

Defining terms

The Knowledge-to-Action (KTA) process represents the process of knowledge creation and its translation into practice and policy. It is considered iterative, dynamic, and complex, concerning both knowledge creation and knowledge application, with the boundaries between the creation and action components and their ideal phases being fluid and permeable. The action phases may occur sequentially or simultaneously and the knowledge phases may influence or be drawn upon during action phases. The cyclic nature of the process and the critical role of feedback loops are key concepts that underlie this conceptual model. While knowledge can be empirically derived (i.e., research based), the framework encompasses other forms of knowing such as contextual and experiential knowledge.

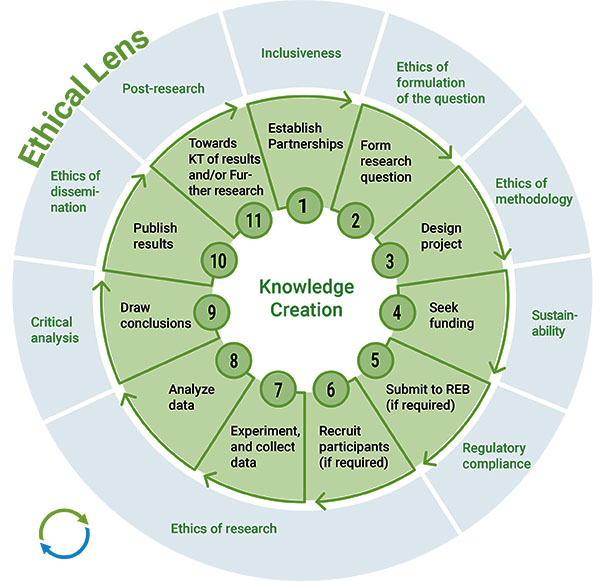

Within KTA, knowledge creation – or the production of knowledge – is composed of three phases: knowledge inquiry (first-generation knowledge), knowledge synthesis (second-generation knowledge), and creation of knowledge tools and/or products (third-generation knowledge). As knowledge is filtered or distilled through each stage in the knowledge creation process, the resulting knowledge becomes more synthesized and potentially more useful to end users.

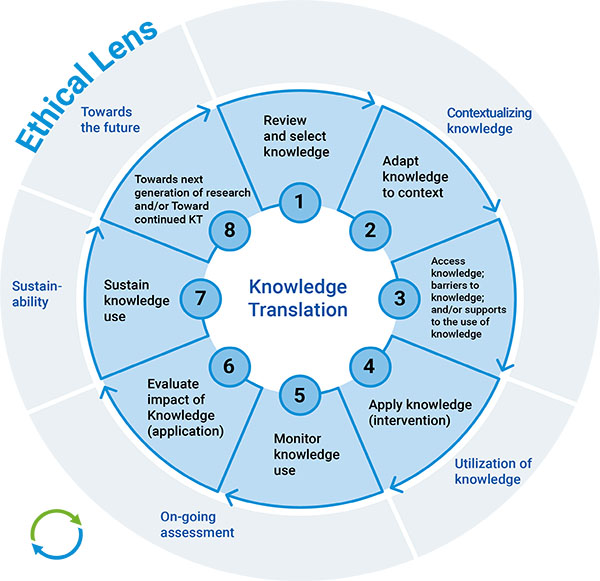

Knowledge translation is formally defined by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research as a dynamic and iterative process that includes the synthesis, dissemination, exchange and ethically sound application of knowledge to improve health, provide more effective health services and products, and strengthen the health care system. This definition has been adapted by others, including Health Canada and the United States National Center for Dissemination of Disability Research and the World Health Organization (WHO)Footnote 2.

Ethics as a critical field of inquiry, has been described in many ways. Most approaches tend to contrast perceived opposites. For instance, a legalistic approach might contrast "right" and "wrong," while an approach to ethics that is grounded in a religious or moral-based perspective would highlight the contrast between what is considered "good" and what is seen as "bad".

In bioethics and research ethics review processes, a ‘principled approach’ is most often used to invoke values that are perhaps as close to universal as is possible, such as beneficence, non-maleficence, autonomy and justiceFootnote 3 in the United States or its Canadian equivalent: respect for persons, concern for welfare, and justiceFootnote 4. This principled approach is invaluable to bioethicists and those conducting research ethics review and oversight, particularly when human participants are involved.

The intent of this material is to help users develop an ‘ethics lens’ without resorting to any particular approach or requiring training in philosophy. The direct application of right/wrong or good/bad dyads in the KTA activities does not help in the identification of the ethical issues, and the principled approach leading to compliance. Another approach is therefore needed. Thus, for the purposes of this Workbook, we will use a pragmatic approach to ethics that is primarily about developing the skills for a critical analysis of relations of power and context. This approach to power and context includes thinking critically about who has power and voice in a specific situation, and who is intentionally or unintentionally silenced; who benefits and who does not; what the consequences of the acts are and in what contexts they occur. Other important ethical aspects are those related to consensual participation in research; responsible use of nature; human and financial resources; respect for human and non-human participants; respect for society; social responsibility of research and researchers; and the importance of creating knowledge as a fundamental aspect of human nature.

This pragmatic approach to ethics asks users of this Workbook simply to consider each element in a given situation and note the potential consequences, rather than to apply any received ideas about good and bad, right or wrong. In other words, the goal of this approach is to develop the practical skills to recognize ethical issues and to decide on the most socially defensible course of action.

Taken together, these understandings of the processes comprising the KTA-cycle, together with a pragmatic approach to ethics, results in the CIHR KTA-Ethics cycle, which is a framework that encompasses the complete lifecycle of scientific knowledge.

Explanation of the CIHR KTA-Ethics Cycle

Figure 1 provides a visual overview of the complete conceptual framework starting with problem identification. The knowledge creation figure (Figure 2) covers topics such as “knowledge inquiry, knowledge synthesis, and knowledge tools/products” (Graham et al., 2006). This phase in the lifecycle of scientific research begins with establishing partnerships and seeking funding and then moves on to the recruiting and data collection phases of research. Some of the ethical issues that can emerge from these topics are highlighted in the tables that accompany each figure. For example, when forming research questions, researchers should be aware of the ways in which contextual factors may influence their choices and how their decisions affect stakeholders, among other things. After data are analyzed, conclusions are drawn, and results are published, the cycle moves towards the knowledge translation of results, which may involve conducting additional research. As the situation warrants, the cycle may either continue with another iteration of knowledge creation, or move towards knowledge translation. The cycle is iterative and may move between knowledge creation and knowledge translation many times in a single inquiry

Topics covered by the Knowledge Translation side of the cycle begin with the process of reviewing and adapting knowledge to a particular context and then selecting and applying that knowledge (Figure 3). Experience gathered through monitoring and evaluating knowledge allows the cycle to move towards the next generation of research and continued knowledge translation.

When taken together, the figures in this section should help the user locate the entirety of their work within the lifecycle of scientific research, identify and think through some of the ethical issues particular to that phase of the cycle, consider how their work relates to earlier and later phases of the cycle, and identify what ethical issues they should anticipate both in the short and longer term.

Diagrams of the CIHR Ethics Cycle

This section provides illustrations of the KTA–E cycle. It is important to note that the explanations shown in the accompanying tables are provided for illustrative purposes only and are not intended to be exhaustive.

Figure 1. The Complete KTA-E Cycle

| Activity | Ethics Lens | |

|---|---|---|

| Identify the Knowledge Creation opportunity or problem |

Problem Identification e.g.

|

|

Figure 2. The Knowledge Creation portion of the KTA-E Cycle

| KC activities | Some Potential Ethical Considerations | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Establish Partnerships | Inclusiveness e.g.

|

| 2 | Form research question | Ethics of formulation of the question

e.g.

|

| 3 | Design project | Ethics of methodology

e.g.

|

| 4 | Seek funding | Sustainability

e.g.

|

| 5 | Submit to REB (if required) | Regulatory compliance

e.g.

|

| 6 | Recruit participants (if necessary) | Ethics of research

e.g.

|

| 7 | Collect data | |

| 8 | Analyse data | |

| 9 | Draw conclusions | Critical analysis

e.g.

|

| 10 | Publish results | Ethics of dissemination

e.g.

|

| 11 | Towards KT (knowledge translation) of results and/or Further research | Post-research e.g.

|

Figure 3. The Knowledge Translation Portion of the KTA-E Cycle

| Knowledge to Action activities | Ethics Lens | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Review and select knowledge | Contextualizing knowledge e.g.

|

| 2 | Adapt knowledge to context | |

| 3 | Access knowledge; barriers to knowledge; and/or supports to the use of knowledge | |

| 4 | Apply knowledge (intervention) | Utilization of knowledge e.g.

|

| 5 | Monitor knowledge use | On-going assessment e.g.

|

| 6 | Evaluate application of knowledge (intervention) | |

| 7 | Sustain knowledge use | Sustainability e.g.

|

| 8a and 8b | Towards next generation of research and/or Toward continued KT (knowledge translation) | Towards the future e.g.

|

- Date modified: