Evaluation of the Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR)

Final Evaluation Report

June 2023

At the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), we know that research has the power to change lives. As Canada's health research investment agency, we collaborate with partners and researchers to support the discoveries and innovations that improve our health and strengthen our health care system.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research

160 Elgin Street, 9th Floor

Address Locator 4809A

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0W9

This publication was produced by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to all participants in this evaluation – survey respondents, key informant interview participants, and Delphi panel participants. Also, thank you to those who supported the evaluation: Kate Benner and Sarah Boorman (Ference and Co.), Eva Maxwell and Kelly Wiens (Gelder, Gingras & Associates), the CIHR SPOR program team, CIHR Funding Analytics, members of the SPOR Working Group and Evaluation Advisory Committee.

The SPOR Evaluation Team

Carmen Constantinescu, Ellie Radke, Bruce Baskerville, Alison Croke, Jean-Christian Maillet, Rachelle Desrochers, Michael Goodyer, and Sarah Connor-Gorber.

For more information and to obtain copies, please contact: evaluation@cihr-irsc.gc.ca.

Table of Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Overview of SPOR Program

- About the Evaluation

- Evaluation Findings

- Conclusions and Recommendations

- Appendix A: Tables

- Appendix B: Figures

- Appendix C: Detailed Descriptions of Core Elements

- Appendix D: Methodology – Additional Details

- Endnotes

List of Tables

- Table 1: CIHR Annual G&A Expenditures on SPOR by Core Element and Unspent Funds, 2010-11 to 2020-2021

- Table 2: CIHR Planned (based on TB submissions) and Actual Operating Costs on SPOR, 2010-11 to 2020-21

- Table 3: SPOR Partners Commitments for Funded Projects

List of Figures

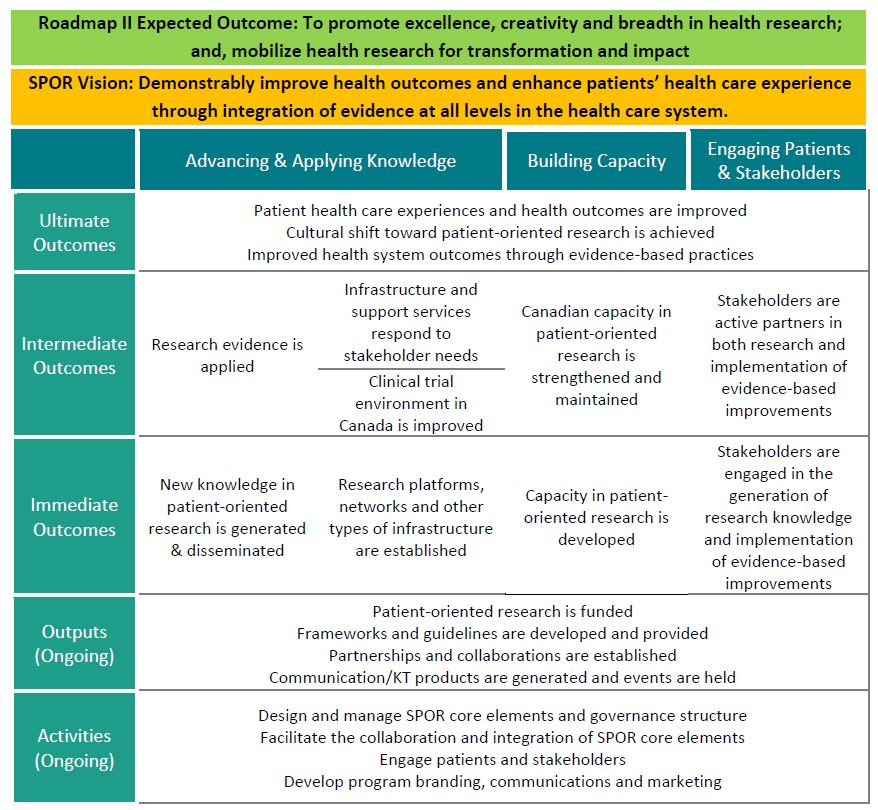

- Figure 1: SPOR Logic Model

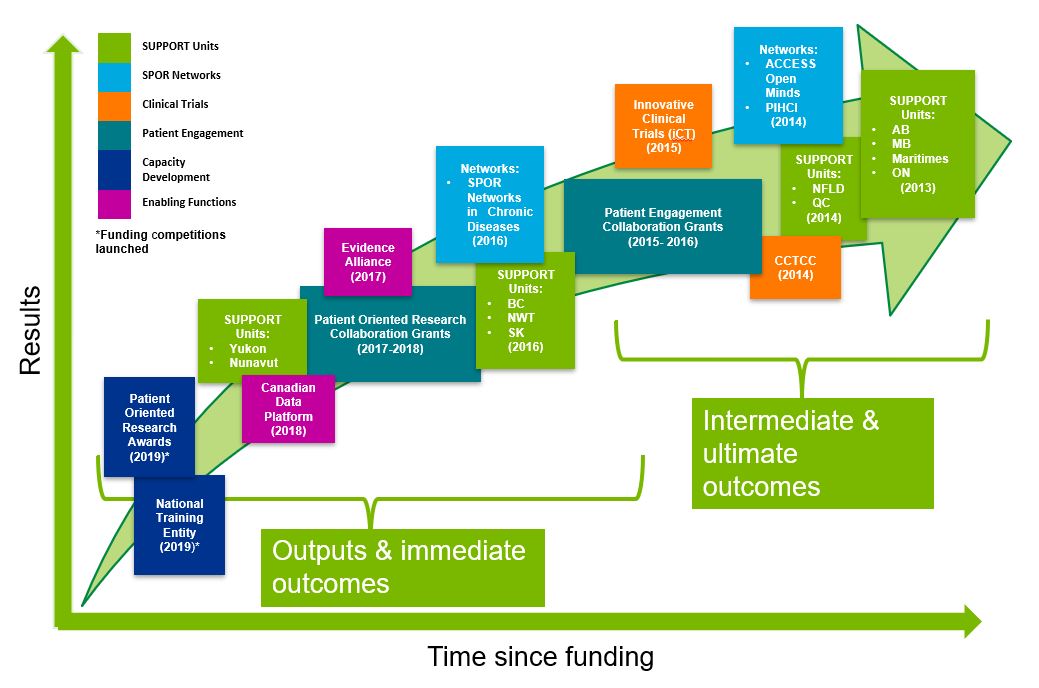

- Figure 2: SPOR Evolution by Core Elements

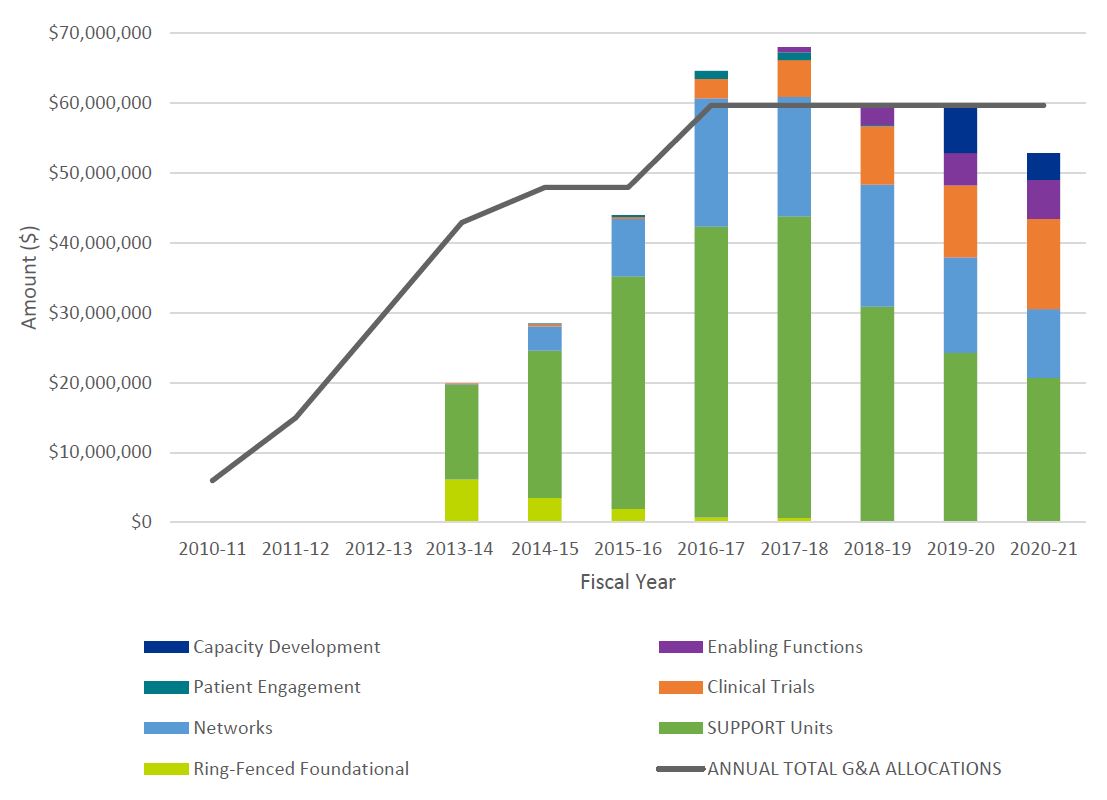

- Figure 3: Annual Allocations from TB and Annual SPOR G&A Expenditures by Core Element

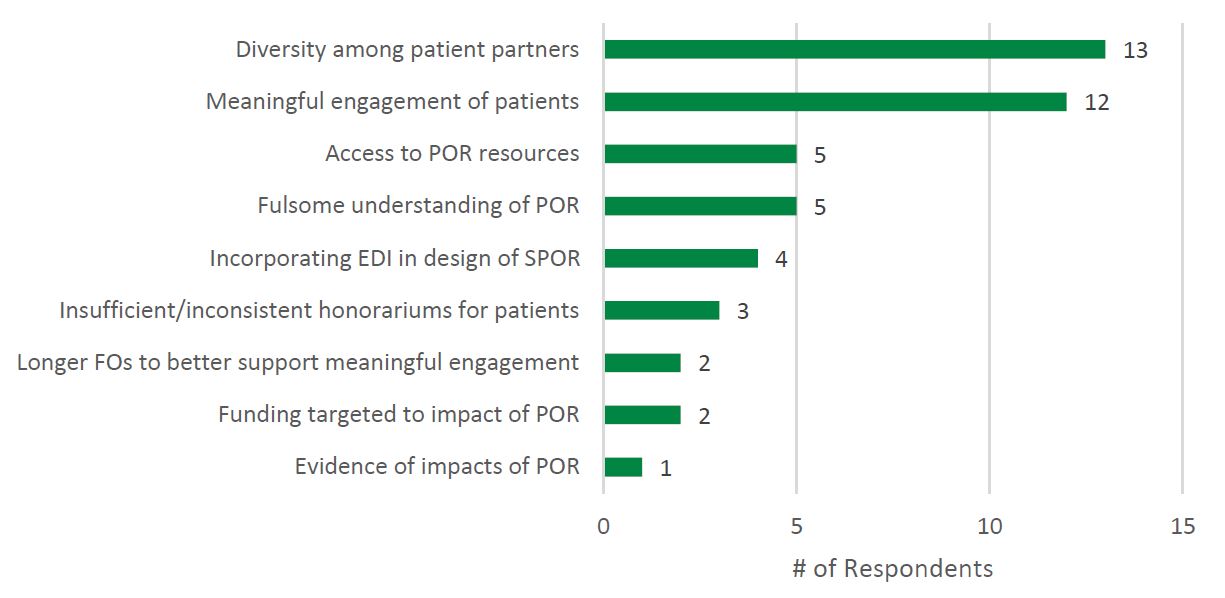

- Figure 4: Needs Not Addressed by SPOR Reported by Researchers

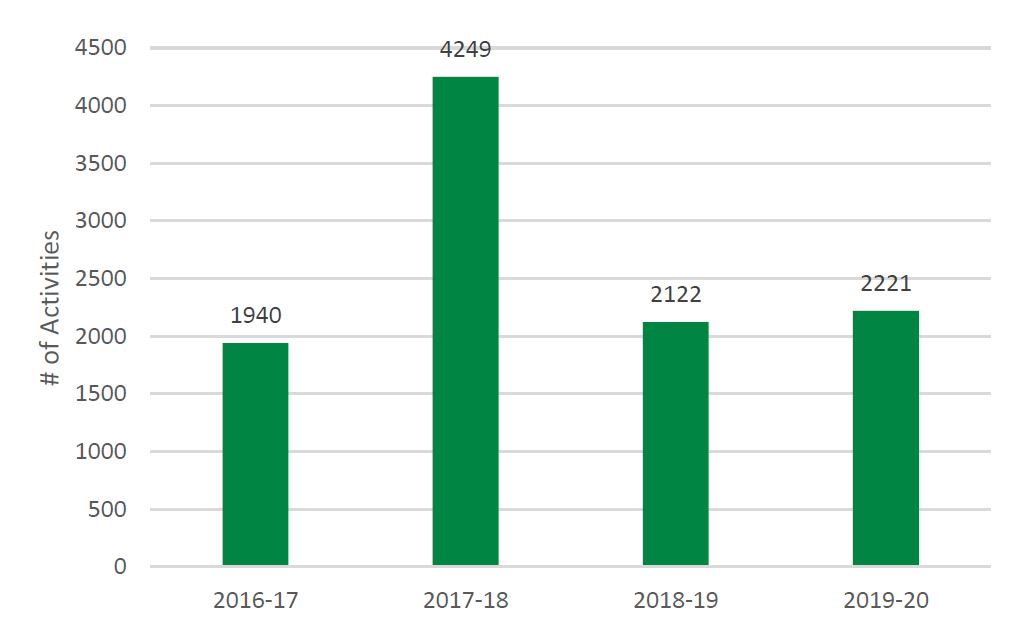

- Figure 5: Number of PE Training or Mentoring Activities Offered by SUPPORT Units, Networks, and SEA, 2016-17 to 2019-20

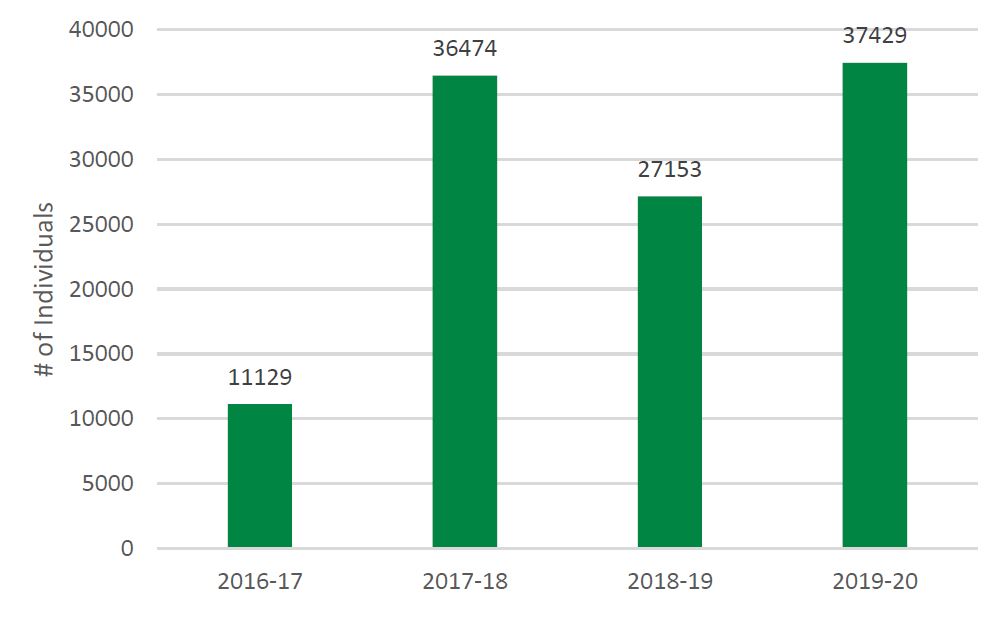

- Figure 6: Number of Individuals Receiving Training or Mentoring in PE by SUPPORT Units, Networks, and SEA, 2016-17 to 2019-20

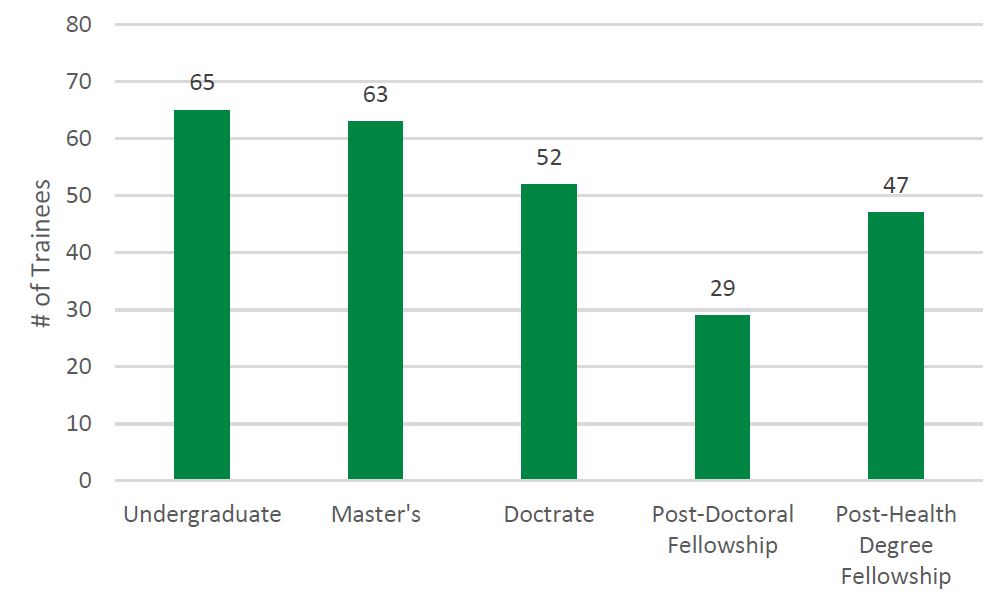

- Figure 7: Number and Type of Trainees Reported by Recipients

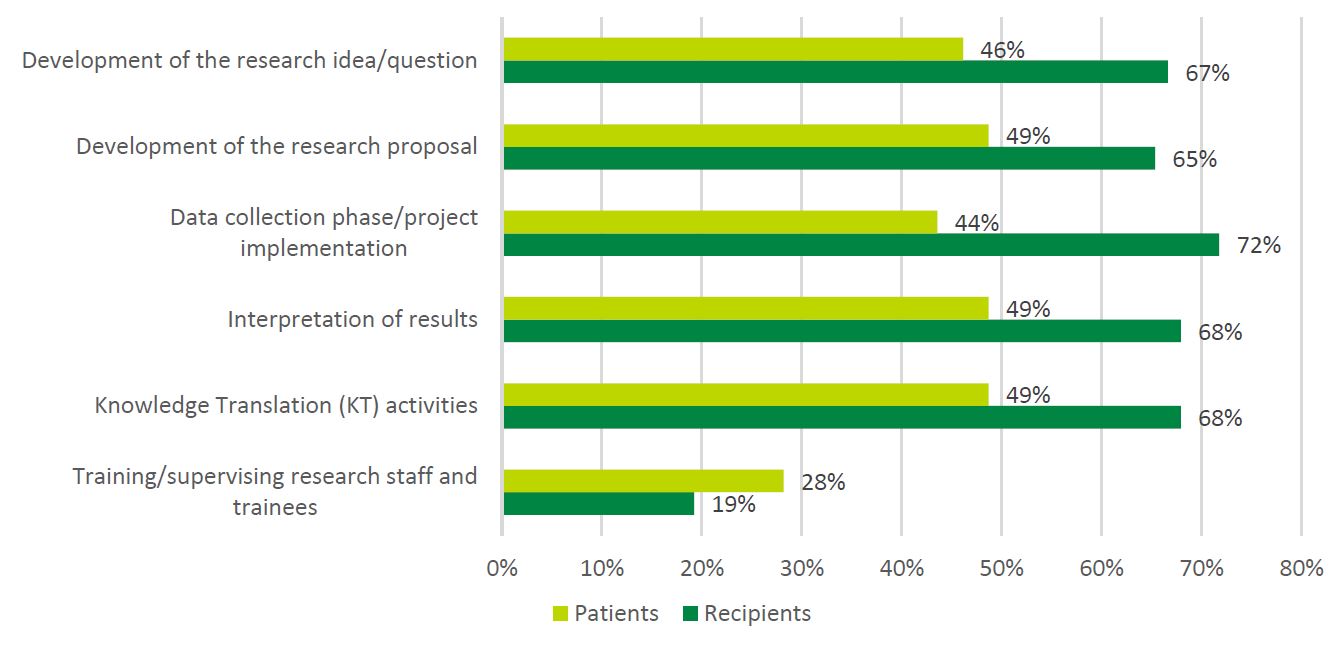

- Figure 8: Patient Involvement Reported by Patients vs. Recipients

List of Acronyms

| Acronym | Meaning |

|---|---|

| ACCESS | Adolescent Connections to Community-Driven Early Strengths-Based Stigma-Free Services |

| Can-SOLVE CKD | Canadians Seeking Solutions and Innovations to Overcome Chronic Kidney Disease |

| CCI | Consumer and Community Involvement |

| CCTCC | Canadian Clinical Trials Coordinating Centre |

| CDP | Canadian Data Platform |

| CIHR | Canadian Institutes of Health Research |

| CTO | Clinical Trials Ontario |

| DAC | Diabetes Action Canada |

| EDI | Equity, Diversity and Inclusion |

| FTE | Full-time Equivalent |

| G&A | Grants and Awards |

| GBA+ | Gender-based Analysis Plus |

| iCT | Innovative Clinical Trials |

| IC/ES | Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences |

| IMAGINE | Inflammation, Microbiome and Alimentum Gastro-intestinal and Neuropsychiatric Effects |

| KT | Knowledge Translation |

| NAPHRO | National Alliance of Provincial Health Research Organizations |

| NSC | National Steering Committee |

| NTE | National Training Entity |

| PCORI | Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Initiative |

| PHAC | Public Health Agency of Canada |

| PIHCI | Primary and Integrated Health Care Innovations |

| POR | Patient-Oriented Research |

| SEA | SPOR Evidence Alliance |

| SGBA+ | Sex and Gender Based Analysis Plus |

| SPOR | Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research |

| SPOR WG | Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research Working Group |

| SUPPORT | Support for People and Patient-Oriented Research and Trials |

| TBS | Treasury Board Secretariat |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

Executive Summary

Program Overview

The Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR) was launched in 2011 by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) as a response to a recognized need for greater uptake of research-based evidence to improve the health of Canadians while improving the cost-effectiveness of the health care system. Patient-oriented research (POR) is intended to focus on priorities that are important to patients and produce information that is taken up and used to improve health care practice, therapies, and policies. The goal of POR is to better ensure the translation of innovative diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to the point of care to ensure greater quality, accountability, and access of care. SPOR offers ongoing funding to support POR in Canada. Through SPOR, CIHR supports POR in Canada together with provincial and territorial ministries of health and other funding partners. SPOR consists of six core elements — Support for People and Patient-Oriented Research and Trials (SUPPORT) Units, SPOR Networks, Clinical Trials, Patient Engagement, Capacity Development, and Enabling Functions – that work to frame, facilitate and fund POR.

Evaluation Objective, Scope and Methodology

The objective of the evaluation is to provide CIHR senior management with valid, insightful, and actionable findings regarding the following:

- Needs addressed by SPOR and the program's alignment with CIHR and Government of Canada priorities;

- Effectiveness of the design and delivery of the program in supporting the achievement of intended outputs and outcomes; and

- Achievement of the program's expected outputs, and immediate, intermediate and ultimate outcomes.

The evaluation covers the period from 2016-17 to 2020-21. This is the second evaluation of the program since it commenced operations in 2011, with the first evaluation completed in 2016. Building on the first evaluation, this evaluation focused on the achievement of intermediate outcomes for elements of SPOR where sufficient time has elapsed and on the achievement of outputs and immediate outcomes for more recently implemented elements. The evaluation was committed to as part of CIHR's 2018-19 Evaluation Plan and designed to meet CIHR's requirements to the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) under the Policy on Results and the Financial Administration Act.

Key Findings

Relevance

There is a continued need to prioritize and foster patient-oriented evidence-informed health care in Canada, with substantive evidence of the relevance and benefits of patient engagement on the research process. POR is key to addressing the need for evidence-informed healthcare in Canada, with partners, patients and knowledge users highlighting its important contributions. There is a need to further increase awareness of both POR and SPOR among members of the health research community, patients, and decision-makers including a shared understanding of the benefits, challenges, and strategies for effective POR.

SPOR is aligned with the roles and responsibilities of the Government of Canada and CIHR's mandate to "excel, according to internationally accepted standards of scientific excellence, in the creation of new knowledge and for the translation of research into improved health for Canadians, more effective health services and products and a strengthened Canadian health care system" (S.C. 2000, c6). SPOR's objectives are well aligned with priorities in both CIHR's current and previous Strategic Plans. CIHR is well positioned to continue to play a leadership role in SPOR, particularly as a research funder and as a coordinating body or convener.

Design and Delivery

SPOR has largely been implemented as planned, with the implementation of SPOR elements evolving with a focus on strategic planning, the development and delivery of new programs and services, and phase II planning for SPOR SUPPORT Units and Networks. The implementation of SPOR has encountered challenges including resourcing limitations; inadequate guidance from CIHR on patient-engagement, including lack of harmonized patient compensation guidelines; uncertainty regarding the grant renewal process; and, challenging internal CIHR partnership processes. The SPOR program has responded to several unexpected shifts in the broader landscape, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, through the core elements demonstrating agility in adapting to the changing needs of patients, researchers, and the broader community. Monitoring of SPOR's implementation continues to be challenged by gaps in financial monitoring of grants and awards (G&A) expenditures, specifically the absence of unique coding for core elements, and operational spending, specifically a lack of information regarding direct salary.

As of 2021-22, the SPOR program had fully implemented actions for three out of six of the recommendations from the first evaluation, completed in 2016, with some actions for three recommendations partially implemented. Actions that remained partially implemented include: strengthening approaches to enable coordination, cross-learning and governance; supporting effective management and administrative functions within and across SUPPORT Units and Networks; and, revising the existing SPOR performance measurement strategy.

In general, the design features of SPOR support the achievement of intended outcomes; however, communication within and across the core elements was identified as inadequate, resulting in duplicative efforts rather than a cohesive approach. SPOR's current approach to patient engagement does not adequately support recruitment of diverse patient partners, with some patient partner groups disproportionately underrepresented in SPOR research. Although core elements demonstrate evidence of engagement with Indigenous community members, Indigenous communities remain underrepresented in SPOR-funded research.

SPOR's governance structure is not meeting its current objectives and lacks adequate patient representation. The National Steering Committee (NSC) has not met in recent years and generally provided advice rather than steering the SPOR program.

While collaboration between CIHR and partners was generally reported to be satisfactory, challenges remain, including: a lack of harmonized patient compensation standards, the need for a safe and supportive sharing environment for patient partners, and opportunities for increased awareness of ongoing SPOR activities.

A comparative review of international POR organizations suggests that using SPOR to inform an organization-wide patient engagement research funding model, in which patient and public engagement in all research programs is either encouraged or mandated, could optimize CIHR's investments in SPOR.

Challenges exist with the current management of performance measurement data including lack of clarity regarding performance indicators, inconsistent or missing indicators, double-counting, introduction of new indicators at the end of the reporting period, burden, and lack of alignment of Network and SUPPORT Unit work plans with the reporting requirements developed by CIHR. There is also limited evidence indicating that performance data are being used to inform decision-making regarding CIHR's implementation and optimization of SPOR.

Performance

SPOR's core elements are contributing to the achievement of immediate outcomes, including the generation of new knowledge, infrastructure, capacity development and engagement of patients and stakeholders. SPOR is generating and disseminating new knowledge as evidenced by the number of Knowledge Translation (KT) productsFootnote 1 produced by the core elements based on the most recent annual reports in scope of the evaluation (2019-20) and trends over the evaluation period. Research platforms and other types of research infrastructure are established by the SUPPORT Units, SPOR Evidence Alliance (SEA) and Canadian Data Platform (CDP) and have responded to the needs of stakeholders by addressing identified barriers to data access and providing necessary evidence to knowledge users to drive decision making. Capacity in POR is developed as evidenced by the 2,221 training activities reaching 37,429 individuals across the SUPPORT Units, Networks and SEA. While there is evidence of engagement of patient partners in all aspects of research, there are opportunities to improve the level of patient engagement in research to avoid the perception of tokenism.

SPOR met or exceeded the 1:1 matching requirement by leveraging $1.16 in planned partner dollars for every CIHR dollar. However, it was not possible to determine if actual applicant partner investments met the matching requirement as applicant partner investments are not captured by CIHR's data systems nor were they systematically compiled from grant reports during the period covered by this evaluation.

SPOR's core elements are contributing to the achievement of intermediate outcomes, however, there are opportunities to strengthen contributions. Research evidence is being applied, as illustrated by guidelines, clinical practice, managerial decision-making, and policy documents citing SPOR-funded research. For example, findings from Primary and Integrated Health Care Innovations (PIHCI) research projects are supporting knowledge users with policy redesign in areas such as centralized waiting lists for primary care and reimagining health care delivery to reduce health care costs. SPOR's infrastructure and support services are aligned with and responding to the needs of stakeholders. Available evidence suggests that progress has been made in improving the clinical trials environment in Canada including the development of infrastructure for clinical trials which is supporting data access and addressing cost, capacity, and efficiency barriers; funding trialists to develop new methods that are low-cost, to generate relevant evidence and catalyze new partnerships and projects; and, supporting patient engagement in clinical trials.

Canadian capacity in POR is being strengthened and maintained, however, there are opportunities to strengthen the capacity for engaging with representative, equitable, and diverse patient populations, for example by re-establishing a governance structure with representation from patients, partners, and funders. Further, patient and stakeholder engagement is contributing to the achievement of intermediate outcomes, with some evidence of Indigenous Communities being active partners in both research and implementation of evidence-based improvements.

SPOR's core elements are contributing to the achievement of a cultural shift towards POR – a key expected ultimate outcome that should be maintained. At this point in time there is little evidence to demonstrate that SPOR has contributed to the expected ultimate outcomes to improve patient health care experiences, health outcomes or health system outcomes.

As expected, the COVID-19 pandemic has had a negative impact overall on recipients' ability to conduct research including reduced laboratory access and opportunities for collaboration.

Recommendations

The evaluation makes six recommendations aimed at improving the performance of SPOR to achieve its expected results.

Recommendation 1:

CIHR should use SPOR to inform an organization-wide approach to patient engagement in research to continue its leadership role, further investment and sustain progress on the outcome of a cultural shift toward POR.

Recommendation 2:

CIHR needs to do the following to improve the program design and delivery of SPOR:

- Increase awareness of the benefits of POR among members of the health research community, patients, and decision-makers.

- Enhance communications among and across SPOR core elements and CIHR institutes to avoid duplicative efforts, promote cohesion, and enhance partnerships.

- Improve overall program monitoring to ensure that research is delivering on intended objectives, such as the engagement of communities and patients in research and provide feedback.

- Establish consistent priorities, mandates and readiness across SPOR core elements to support linkages, alignment and coordination of initiatives.

Recommendation 3:

CIHR should re-establish an external and internal governance structure for SPOR with defined roles and responsibilities, including better representation from patients, partners, and funders, to improve CIHR's decision-making on SPOR.

Recommendation 4:

CIHR needs to improve patient and community engagement both in SPOR and in research in the following manner:

- Embed equity, diversity and inclusion considerations into the recruitment of patient partners to address the underrepresentation of important patient partner groups in research.

- Harmonize patient compensation standards across SPOR.

- Enhance accountability for meaningful patient engagement.

- Ensure consistency in engagement of Indigenous community members across SPOR core elements.

Recommendation 5:

CIHR should improve the management and reporting of SPOR performance measurement data to better inform decision-making by establishing a clear set of measures to track progress expected outcomes related to patient health care experiences, health, and health system.

Recommendation 6:

CIHR needs to further improve the following aspects of its financial monitoring and coding for SPOR:

- Grants and awards expenditures, especially coding of core elements and tracking of partner contributions.

- Operating and maintenance expenditures, specifically direct salary costs.

Overview of SPOR Program

Program Description

The Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR) was launched in 2011 by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) as a response to a recognized need for greater uptake of research-based evidence to improve the health of Canadians while improving the cost-effectiveness of the health care system. Patient-oriented research (POR) is intended to focus on priorities that are important to patients and produce information that is taken up and used to improve health care practice, therapies, and policies. The goal of POR is to better ensure the translation of innovative diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to the point of care to ensure greater quality, accountability, and access of care. SPOR offers ongoing funding to support POR in Canada. Through SPOR, CIHR supports POR in Canada together with provincial and territorial ministries of health and other funding partners.

Concretely, SPOR aims to achieve the followingFootnote 2 (see Figure 1: SPOR Logic Model):

- For patients, it means having a say in which health topics are researched;

- For researchers, it means benefiting from the perspectives and experiences of patients; and

- For the health care system, it means having access to the research evidence that decision-makers and health care providers need to improve care.

SPOR adheres to the following principles:

- Patients are involved in all aspects of research;

- Decision-makers and clinicians are involved throughout the entire research process to ensure integration into policy and practice;

- CIHR funding for SPOR initiatives is matched 1:1 with non-federal funding partners;

- Effective POR requires a multi-disciplinary approach; and

- Performance measurement and evaluations are integral components.

SPOR consists of six core elements — Support for People and Patient-Oriented Research and Trials (SUPPORT) Units, SPOR Networks, Clinical Trials, Patient Engagement, Capacity Development, and Enabling Functions – that work to frame, facilitate and fund POR. The first two years following the launch of the Strategy were focused on implementation design, including establishing a National Steering Committee (NSC), determining priorities, and creating funding opportunities for some of the core elements. The implementation of the different SPOR core elements began in 2013-14 when funding was initiated for four of the SUPPORT Units, two of the Networks, and the Canadian Clinical Trials Coordinating Centre (CCTCC). In the following years, more components of the core elements were implemented including: the Innovative Clinical Trials (iCT) Initiative, five additional SUPPORT Units, five more networks in Chronic Diseases, Patients Engagement Collaborations Grants, two enabling functions (i.e., the SEA and the CDP) and two capacity building components (i.e., the Patient-Oriented Research Awards and the National Training Entity). Additional details on SPOR's core elements are provided in Appendix C: Detailed Descriptions of Core Elements.

About the Evaluation

Purpose and Scope

The purpose of this evaluation is to provide CIHR senior management with valid, insightful, and actionable findings regarding the following:

- Needs addressed by SPOR and the program's alignment with CIHR and Government of Canada priorities;

- Effectiveness of the design and delivery of the program in supporting the achievement of intended outputs and outcomes; and

- Achievement of the program's expected outputs, and immediate, intermediate and ultimate outcomes.

By addressing these issues, the evaluation will help inform CIHR senior management decision-making and planning regarding the SPOR program, and meet the evaluation requirements outlined in the Policy on Results and subsection 42.1 of the Financial Administration Act.

The evaluation of the SPOR program was conducted by the CIHR Evaluation Unit and covers the period from 2016-17 to 2020-21 (with the extent of coverage of various elements dependent on when the elements were initiated; see Figure 2: SPOR Evolution by Core Elements). The extent to which the program has achieved its expected intermediate outcomes was measured by examining SPOR elements where sufficient time has elapsed. The extent to which outputs and immediate outcomes have been achieved was measured through more recently implemented elements. The evaluation design used a comprehensive approach with numerous lines of evidence to maximize depth of coverage of evaluation questions and rigour, and to triangulate data.

Evaluation Context

Previous Evaluation

This is the second evaluation of the SPOR and builds upon the first SPOR evaluation completed in 2016 which covered the period from inception in 2010-11 to 2015-16.

The findings from the first evaluation supported the continued need for the SPOR program, and its alignment with roles and responsibilities of the federal government and mandates of CIHR. The first evaluation made the following recommendations, agreed to by CIHR senior management in a management response to the evaluation:

- CIHR should increase efforts to strengthen SPOR's role in a common agenda for change to POR.

- CHIR should provide strategic guidance regarding how SPOR elements are to work together toward achieving SPOR's intermediate and long-term outcomes.

- CIHR should communicate plans for moving beyond the initial five-year funding period to manage sustainability expectations for CIHR investments in SPOR.

- CIHR should strengthen approaches to enable cross-learning, sharing of best practices, and collaboration; this should occur within and across SPOR elements and between CIHR and Canadian and International organizations.

- CIHR should continue to support effective management and administrative functions within funded SPOR SUPPORT Units and Networks and across these elements.

- CIHR should revise the existing SPOR performance measurement strategy to balance administrative/operational outputs with outcomes/impacts.

The current evaluation builds on the first evaluation to understand the effects of the actions taken in response to these recommendations, assess the achievement of immediate outcomes and, given that the program has been implemented for a decade, examine progress towards the achievement of intermediate and ultimate outcomes.

Evaluation Methodology

Evaluation Questions

The evaluation addresses the following specific questions.

Relevance

- To what extent is there a continued need to prioritize and foster patient-oriented evidence-informed health care in Canada?

- To what extent is POR relevant to addressing this need?

- To what extent has the role of the federal and provincial/territorial governments in SPOR been aligned with their respective roles and responsibilities in health care?

- To what extent is SPOR aligned with CIHR's mandate?

Design and Delivery

- To what extent has SPOR been implemented as planned?

- How has SPOR been responsive to shifts in the broader landscape or needs identified by SPOR partners?

- How have recommendations from the 2016 formative evaluation of SPOR been addressed (e.g., sustainability, collaboration between core elements, performance measurement)?

- How do the design features of SPOR (six core elements, principles) support the achievement of SPOR's intended objectives?

- How and to what extent are interconnections among the core elements fostered?

- How effectively has the governance structure for SPOR (i.e., SPOR NSC, SPOR WG) guided the implementation of the strategy?

- To what extent has collaboration between CIHR and partners/stakeholders been satisfactory and effective?

- To what extent have communications around SPOR been satisfactory and effective?

- What alternative models or approaches could optimize CIHR's investment in SPOR?

Performance

- How and to what extent are the six core elements of SPOR contributing to the achievement of immediate outcomes?

- New knowledge in POR is generated and disseminated.

- Research networks, platforms and other types of research infrastructure are established.

- Capacity in POR is developed.

- Patients and other stakeholders are engaged in the generation of research knowledge and implementation of evidence-based improvements.

- To what extent are the six core elements of SPOR contributing to the achievement of intended intermediate outcomes?

- Research evidence is applied.

- Infrastructure and support services respond to stakeholder needs.

- Clinical trials environment in Canada is improved.

- Canadian capacity in POR is strengthened and maintained.

- Patients and other stakeholders are active partners in both research and implementation of evidence-based improvements.

- To what extent are the six core elements of SPOR contributing to achieving intended ultimate outcomes?

- Patient health care experiences and health outcomes are improved.

- Cultural shift toward POR is achieved.

- Improved health system outcomes through evidence-based practices.

- To what extent has the COVID-19 pandemic impacted the delivery and performance of SPOR?

- Negative and positive consequences at the individual, research activity and strategy levels (e.g., lessons learned from pivoting to new ways of operating and trying to develop new solutions for primary health care and health research);

- Future anticipated changes to SPOR and SPOR-related research activity (e.g., innovations in virtual care will look post-pandemic era); and

- The effect that COVID-19 had on scientific productivity by gender, age, and other factors.

Evaluation Approach

The evaluation employed both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods and analyses. Consistent with best practices in program evaluationFootnote 3 as well as the Policy on Results, multiple lines of evidence were used to triangulate evaluation findings. This included a document review; administrative data review; an environmental scan; a bibliometric analysis; and surveys of recipients (n = 89), applicants (n = 49), and stakeholders of the program (n = 155), including co-applicants (n = 50), patient partners (n = 39)Footnote 4, trainees (n = 39), other partners (n = 16)Footnote 5, knowledge users (n = 11). There were also key informant interviews (n = 38) conducted with SPOR program management (n = 13), patient partners (n = 9), other partners (n = 9), knowledge users (n = 4), POR experts (n = 3); case studies (n = 5); and a Knowledge Readiness Levels analysis.

Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA+) and equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) considerations were built into the evaluation framework via specific evaluation questions and indicators.

Note that the reported denominator will change as it reflects the number of individuals who were posed the question. Given the large number of lines of evidence with varying sample sizes, the following qualifiers have been used to indicate the frequency of responses for some lines of evidence conducted, for consistency (i.e., surveys and key informant interviews). It is important to note that these qualifiers have been used in order to summarize statements about qualitative data; they should not necessarily serve as a measure of the importance of the respective finding.

| None | A few | Some | Many | Most | Almost all | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (0 or no) | (<20%) | (20-39%) | (40-59%) | (60-79%) | (80-99%) | (100%) |

Additional details about the methodology are provided in Appendix D: Methodology – Additional Details.

Limitations of this Evaluation

The evaluation leveraged a variety of data sources. The value of this evidence-based strategy lies in the efficiency of utilizing currently available data and synthesizing it through a single evaluative lens. However, as with all evaluations, this evaluation encountered some limitations (discussed in more detail in Appendix D: Evaluation Limitations and Mitigation Strategies). The main limitations associated with this evaluation are:

- Limited ability in attributing changes at the intermediate and ultimate outcome level to SPOR due to the complexity of the SPOR initiative and the health research funding landscape;

- Staggered timelines of implementation of the SPOR elements;

- Availability of data (i.e., limited ability to develop complete listings of researchers, trainees, patients, partners, and other stakeholders of SPOR);

- Analyzing performance and other secondary data sources (e.g., self-report data, possible double-counting, possible incompleteness); and

- Limited counterfactual (i.e., given there is no similar Canadian program, the only population for a counterfactual approach was researchers who applied, but did not receive, SPOR funding).

Evaluation Findings

Relevance

Key Findings:

- There is a continued need to prioritize and foster patient-oriented evidence-informed health care in Canada, with substantive evidence of the relevance and benefits of patient engagement on the research process.

- POR is key to addressing the need for evidence-informed healthcare in Canada, with partners, patients and knowledge users highlighting its important contributions.

- Further awareness of both patient-oriented research and SPOR is needed, including a shared understanding of the benefits, challenges, and strategies for effective patient-oriented research among members of the health research community, patients, and decision-makers.

- SPOR is aligned with the roles and responsibilities of the Government of Canada and CIHR's mandate to "excel, according to internationally accepted standards of scientific excellence, in the creation of new knowledge and for the translation of research into improved health for Canadians, more effective health services and products and a strengthened Canadian health care system."

- SPOR's objectives are well aligned with all five of CIHR's Strategic Plan priorities to advance research excellence in all its diversity, strengthen Canadian health research capacity, accelerate the self-determination of Indigenous Peoples in health research, pursue health equity through research and to integrate evidence in health decisions.

- CIHR is well positioned to continue to play a leadership role in SPOR, particularly as a research funder and as a coordinating body or convener.

There is a continued need to prioritize and foster patient-oriented evidence-informed health care in Canada.

It is evident that there is a continued need to prioritize and foster patient-oriented evidence-informed health care in Canada, with substantive evidence of the benefits of patient engagement on the research process. The need for POR is supported by considerable literature on patient partnership and community engagement in the production of evidence, the identified benefits engagement or patient involvement brings to the research process, and the work on principles and best practices that has been done to address the challenges in conducting POR. Evidence-based medicine has identified patient partnership in the production of evidence as one of the key ways of developing more trustworthy evidence and it has been described as a moral imperative that is associated with a number of benefits and challenges (Gill & Cartwright, 2021). A review of recent literature revealed key benefits of POR on the research process, including more relevant research topics and priorities, more relevant research outcomes, and uptake of evidence by health policy decision-makers. Benefits that were specific to patients included empowerment, prioritization of research relevant to the community, enhanced knowledge and skills, increased transparency and accountability, and more useful evidence for the purpose of knowledge translation (KT) (Vat et al., 2020).

POR is key to addressing the need for evidence-informed healthcare in Canada.

Survey findings and key informant interviews indicate that POR, through SPOR, is key to addressing the need for evidence-informed healthcare in Canada, with partners, patients and knowledge users highlighting its important contributions. On a 5-point scale from Not at All to a Very Great Extent, SPOR researchers and stakeholders surveyed felt that SPOR is addressing the need for POR in Canada to a moderate-to-great extent (Recipients: M = 3.8 out of 5, SD = 1.1, n = 84; Stakeholders: M = 4.1 out of 5, SD = 1.1, n = 165). Almost two-thirds of SPOR researchers indicated that their research project would not have proceeded had they not received SPOR funding (Recipients: 62%, n = 54), and indeed, almost two-thirds of unsuccessful applicants indicated that their POR project either did not proceed or had to be modified as a result of not receiving SPOR funding (66%, n = 31), emphasizing both the need for and importance of SPOR funding in supporting POR in Canada. Almost all key informants (25/30) indicated the continued need for POR in supporting evidence-informed health care, with partners, patients and knowledge users highlighting its important contributions, including capacity building, partnership and collaborations, engagement in decision-making and improvements to healthcare. Some key informants (9/26) reported that SPOR does not duplicate, but rather complements other patient engagement research activities across Canada.

"[The] patient population is still completely unaware that these [SPOR] opportunities exist."

Further awareness of both patient-oriented research and SPOR is needed, including a shared understanding of the benefits, challenges, and strategies for effective patient-oriented research among members of the health research community, patients, and decision-makers. Documents reviewed, key informants and SPOR researchers surveyed cited challenges or needs not generally being met by existing POR supports. A review of recent literature on the relevance of POR identified a number of potential challenges associated with POR, including challenges in the selection of patient partners; tokenism; logistical and practical barriers; patient exclusion from research stage; insufficient knowledge; absence/impact of patient compensation; traditional research culture; and challenges in participant recruitment (Martineau et al., 2020). Lack of awareness of SPOR was mentioned by some key informants (8/29) and two survey respondents, including comments that the SPOR program needs to continue to be communicated to patients, researchers, and decision-makers, with a few proposing that POR be integrated across all CIHR's granting activities.

SPOR is aligned with the roles and responsibilities of the federal government as well as CIHR strategic priorities.

There is evidence of an identified role for the federal government in supporting evidence-informed health care, with government mandate released during the evaluation reporting period emphasizing the importance of responding rapidly to ongoing changes in the healthcare system. The 2017 Mandate Letter from the Minister of Health communicated a need to keep up with advances in health technology that are rapidly changing health care across Canada and need for the federal government to continuously be a part of improving outcomes and quality of care for Canadians (Government of Canada, 2017). More recently, the 2021 Speech from the Throne outlined the need to strengthen the healthcare system for all Canadians, particularly seniors, veterans, persons with disabilities, vulnerable members of our communities, and those who have faced discrimination (Government of Canada, 2021b).

In terms of its alignment with CIHR, SPOR's objectives are very well aligned with the CIHR Act, CIHR's mandate, and CIHR's Strategic Plan priorities. SPOR's objective to improve care by integrating research evidence into the health care system is aligned with the CIHR Act (S.C. 2000, c6) as it acknowledges the importance of supporting initiatives that will lead to the improved health of Canadians. This objective is also aligned with CIHR's mandate for translation of research into improved health for Canadians, more effective health services and products and a strengthened Canadian health care system.

SPOR aligns with CIHR's Strategic Plan 2014-15 to 2018-19, Health Research Roadmap II: Capturing Innovation to Produce Better Health and Health Care for Canadians, as well as CIHR's Strategic Plan 2021-2031, a Vision for a Healthier Future. SPOR's principle to involve patients in all aspects of research aligns with Strategic Direction 2 of CIHR's Strategic Plan for 2014-15 to 2018-19, to mobilize health research for transformation and impact through its intent to build, shape and mobilize research capacity to address critical health issues that are important to patients and Canadians (CIHR, 2015). Additionally, SPOR is specifically mentioned as a means of incorporating POR into policy and practice within Research Priority A: enhancing patient experiences and outcomes through evidence-informed health innovations. Further, the objectives of SPOR are closely aligned with all five priorities of CIHR's new Strategic Plan (CIHR, 2021). Specifically, Priority E to integrate evidence in health decisions cites the creation of SPOR as helping to shape the field of knowledge mobilization in Canada and moving evidence into Canadian health systems.

CIHR is well-positioned to play a leadership role in SPOR.

Almost all key informants (30/35) expressed that CIHR is well-positioned to play a leadership role in SPOR. In addition to being the major health research funder in Canada, areas where CIHR is best positioned to extend its leadership role include that of a national convener that brings stakeholders together to ensure that patient engagement is integrated across the research cycle. In addition, key informants described CIHR as a catalyst for patient engagement in research that includes such things as supporting KT, developing methodologies and protocols and best practices, creating patient engagement tools for researchers, an honest broker for the provincial and territorial jurisdictions, building capacity in POR, and setting the standards for guidelines and policies for such matters as patient compensation.

Design and Delivery

Key Findings:

- SPOR has largely been implemented as planned, with the implementation of SPOR elements evolving with a focus on strategic planning, the development and delivery of new programs and services, and phase II planning for SPOR SUPPORT Units and Networks.

- The implementation of SPOR has encountered challenges including resourcing limitations within the SPOR team; inadequate guidance from CIHR on patient-engagement, including lack of harmonized patient compensation guidelines; uncertainty regarding the grant renewal process; and challenging internal CIHR partnership processes.

- Assessing implementation continues to be challenged by gaps in financial monitoring of G&A expenditures and operational spending due to the absence of unique coding for core elements as well as limited ability to robustly determine the number of Full-time Equivalent (FTE) CIHR employees contributing to SPOR activities.

- The SPOR program has responded to several unexpected shifts in the broader landscape, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, through the core elements demonstrating agility in adapting to the changing needs of patients, researchers, and the broader community.

- In general, the design features of SPOR support the achievement of intended outcomes; however, communication within and across the core elements was identified as inadequate, resulting in duplicative efforts rather than a cohesive approach.

- While collaboration between CIHR and partners was generally reported to be satisfactory, challenges remain, including: a lack of harmonized patient compensation standards, the need for a safe and supportive sharing environment for patient partners, and opportunities for increased awareness of ongoing SPOR activities.

- SPOR's current approach to patient engagement does not adequately support recruitment of diverse patient partners, with some patient partner groups disproportionately underrepresented in SPOR research.

- Although core elements demonstrate evidence of engagement with Indigenous community members, Indigenous communities remain underrepresented in SPOR research.

- SPOR's governance structure is not meeting its current objectives and lacks adequate patient representation. The NSC has not met in recent years and generally provided advice rather than steering the SPOR program.

- A comparative review of international POR organizations suggests that using SPOR to inform an organization-wide patient engagement research funding model, in which patient and public engagement in all research programs is either encouraged or mandated, could optimize CIHR's investments in SPOR.

- As of 2021-22, the SPOR program had fully implemented actions for three out of six of the recommendations from the first evaluation, completed in 2016, with some actions for three recommendations partially implemented. During the period under review, the following actions remained partially implemented:

- Strengthen approaches to enable coordination, cross-learning and governance;

- Support effective management and administrative functions within and across SUPPORT Units and Networks; and,

- Revise the existing SPOR performance measurement strategy.

- Challenges exist with the current management of performance measurement data including lack of clarity regarding performance indicators, inconsistent or missing indicators, double-counting, introduction of new indicators at the end of the reporting period, burden, and lack of alignment of Network and SUPPORT Unit work plans with the reporting requirements developed by CIHR.

- There is also limited evidence indicating that performance data are being used to inform decision-making regarding CIHR's implementation and optimization of SPOR.

SPOR has largely been implemented as planned.

A review of documentation and key informant interviews revealed that SPOR has been largely implemented as planned, with the implementation of SPOR elements evolving with a focus on strategic planning, the development and delivery of new programs and services, and phase II planning for SPOR SUPPORT Units and Networks. Administrative data indicates that SPOR evolved from initial planning stages and the solidifying of partnerships in 2011 to the funding of SPOR core elements starting in 2013-14. The first two years following the launch of the Strategy were focused on implementation design, including establishing a National Steering Committee (NSC), determining priorities, and creating funding opportunities for the first core elements. The implementation of the different SPOR core elements began in 2013-14, when funding was initiated for four of the SUPPORT Units (Alberta, Manitoba, Maritimes, and Ontario), two of the Networks (Adolescent Connections to Community-driven Early Strengths-based Stigma-free Services [ACCESS] Open Minds and the Primary and Integrated Health Care Innovations [PIHCI] Network), and the Canadian Clinical Trials Coordinating Centre (CCTCC). In the following years, more components of the core elements were implemented including: the innovative Clinical Trials (iCT) Initiative, five additional SUPPORT Units, five more Networks (Chronic Disease), Patient Engagement Collaborations Grants, two enabling functions (the SPOR Evidence Alliance [SEA] and the Canadian Data Platform [CDP]) and two capacity building components (the Patient Oriented Research Awards and the National Training Entity [NTE]). Further, phase II funding has begun for some Networks and SUPPORT Units, such as the Alberta SUPPORT Unit and the CDNs. Figure 2: SPOR Evolution by Core Elements depicts the implementation of components of the SPOR core elements at different points in time.

SPOR expenditures increased as new elements were added over time, starting at $14.4M in 2013-14 with a peak at $67.6M in 2017-18, and remaining stable at approximately $60M per year for the period 2018-2021. Following significant underspending on G&A in the period of the first evaluation while implementing the strategy, CIHR has consistently spent 89% or more of its allocation from Treasury Board (TB) within the fiscal year, including overspending in years 2016-17 and 2017-18, resulting in $6M (10%) in additional G&A spending beyond what was allocated to CIHR by TB. SUPPORT Units have received the highest levels of investment, totaling $228M, followed by Networks $88M, Clinical Trials $40M, Enabling Functions $13M, Capacity Development $10M and Patient Engagement $2.8M (Figure 3: Annual Allocations from TB and Annual SPOR G&A Expenditures by Core Element). The total cumulative expenditures for the SPOR program for the period of 2010-2021 was $390,981,571.

The first evaluation of SPOR reported a consistent decrease in Foundational InvestmentsFootnote 6 as SPOR focused its efforts on the core elements. Whether this trend continued could not be assessed since the Foundational Investments made using funding outside the SPOR Ring-Fenced funding were not included in financial reporting on the SPOR program past the period of the first SPOR evaluation (Table 1: CIHR Annual G&A Expenditures on SPOR by Core Element and Unspent Funds, 2010-11 to 2020-21). The evaluation team was unable to find documentation to confirm the nature of the investments (programs and grants), and if those investments ended in fiscal year 2015-16 or continued thereafter.

Several challenges to implementation were identified within program documentation and key informant interviews. Inhibiting factors identified in program documentation and supported by key informant interviews included uncertainty of funding (2/14) and staffing challenges (i.e., under-resourcing leading to stress completing annual operations such as annual reporting, daily operations, and grant renewals at the core element level, and inability to provide timely feedback on annual reports at the program management level (2/14). The most frequently reported inhibiting factor from the document review was the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as patient partner turnover, a health system transformation, delays with data access, and the implementation of a new strategic plan for the data platform and services component requiring a greater demand of resources. CIHR staff, SPOR entity leads, and knowledge users interviewed also identified CIHR not providing enough guidance on patient engagement policies or standards (4/14) or holding grant recipients to a patient engagement standard (2/14), and that the internal CIHR partnership processes among SPOR entities could be improved (4/14).

The review of administrative data indicate that, while the SPOR program overspent its planned operating expenditures considerably in early years of the program, annual operational spending has remained within 92% and 108% of the allocations from TB since 2016-17 (Table 2: CIHR Planned (based on TB submissions) and Actual Operating Costs on SPOR, 2010-11 to 2020-2021).

The administrative costs for SPOR are derived from a combination of actual expenditures and estimates of direct salary costs. In the case of FTEs and salary costs, the reported total FTE estimate was consistently lower (ranging from 20.05 to 23.1) than the 27.75 planned FTEs for SPOR for the period under review (2016-17 to 2020-21). However, the lower number of reported FTEs did not result in reduced operational spending due to the salary costs of the number of senior professional positions reported. CIHR does not have a robust method to track staff time associated with SPOR activities across the entire organization. Therefore, for the purpose of this evaluation, Financial Planning and Advisory Services asked the SPOR staff to review the list of positions used to derive the planned 27.75 FTEs in the first evaluation and provide an estimated FTE for those positions for each year from 2016-17 to 2020-21. It should be noted that due to time constraints these estimates were not validated by the implicated CIHR business units, and the mid-range salary for each position was used to estimate direct salary costs.

The estimated total cost of administering the SPOR Program as a percentage of Total Program Expenditures varied between 6.2% and 7.5% over the period of the evaluation. This is high relative to CIHR overall, which has an average of 5.4%, but is lower than SPOR's planned administrative costs percentage of 7.7%. It is important to note that the validity of this estimate is affected by the method used to estimate FTEs contributing to SPOR.

SPOR has been responsive to shifts in the broader landscape.

According to documents reviewed and key informant interviews, the SPOR program has been responsive to several unexpected shifts in the broader landscape, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, through the core elements demonstrating agility in adapting to the changing needs of patients, researchers, and the broader community. Many core elements stated in program documentation that the pandemic resulted in temporary closures to a few of their partner institutions (e.g., Memorial University), unplanned and unforeseen staffing departures and leaves of absence, as well as some projects and events being placed on hold (e.g., the Canadian Association for Health Services and Policy Research conference). Many SPOR core elements, including SUPPORT Units, Networks and the CDP reported shifting priorities to address the urgent needs of health policy and practice due to COVID-19, while simultaneously maintaining important non-COVID-19 research. Since the start of the pandemic, documentation from core elements revealed how agile they were in meeting unexpected requests for support from within each province while maintaining regular functions.

Funding uncertainty was another frequently cited reason for changes to the SPOR program among documentation reviewed. Sustainability and succession planning have been challenging for some of the SPOR SUPPORT Units and Networks given funding uncertainty for health research and POR from both federal and provincial sources. Due to the grant funding coming towards the end of its first cycle, one SUPPORT Unit reported losing several staff to local industries where they could be offered more job security, which led to the loss of some institutional memory. The core elements through program documentation indicated that they have been quick in replacing some of these staff and ensuring that there is cross training of staff to cover vacancies. With the second bridge period from CIHR in place, some of the SUPPORT Units felt they were better able to advocate for continued support for several of its partnered POR supports.

With the publication of the new SPOR II guidelines and associated funding envelopes it became clear that some SUPPORT Units would need to become a leaner team, this resulted in several individuals being given their notice. Staff changes always cause some degree of upset to workflow however the Units reported that remaining team members have continued to work efficiently, and priorities have been adjusted to ensure that all the required work is being completed in a timely manner. Additionally, retention of patient partners has required some flexibility on the part of the core elements. A number of patient partners were elderly and considering leaving their home province to be with family. For example, to adapt to the potential loss of patient partners, the Patient Advisory Council in Newfoundland was tasked with developing a patient partner recruitment and retention policy.

Some key informants (10/29) indicated that SPOR had sufficient flexibility to respond to changing environment or landscape and identified needs. One partner expressed how SPOR has taken projects from an idea to a competitive stage and one patient partner expressed that CIHR did a good job educating patients on what to expect from participating in research. Some key informants (13/35) also reported that SPOR adapted in response to patient partner needs. For example, elements of projects were modified or adapted according to the input and needs of patients and SPOR continued to adapt by responding to identified gaps, such as the need for capacity building and through the process of co-creation with patients.

Design features support the achievement of intended outcomes.

Overall, program documentation revealed that SPOR's core elements are supporting the achievement of the program's intended outcomes. Long-standing entities, including the SUPPORT Units, Networks, and iCT support the achievement of both SPOR's immediate and intermediate outcomes. SUPPORT Units provide decision-makers and health care providers with the means to connect research with patient needs so that evidence-based solutions can be applied to health care and then shared throughout the country. They also generate new knowledge in POR, exist as established infrastructure across Canada, develop the capacity for POR in Canada, and engage stakeholders in the generation of research and implementation of evidence-based improvements. Similarly, Networks support the achievement of intermediate outcomes, including playing a key role in capacity development aimed at fostering the next generation of patient-oriented researchers. They also contribute to SPOR's intermediate outcomes by focusing on specific health challenges identified as priorities in multiple provinces and territories and generating evidence and innovations designed to improve patient health and health care systems. This supports research evidence being applied and responding to stakeholder needs. The iCT contributes to immediate outcomes, including supporting trialists to develop new POR methods that are low-cost, expected to generate relevant evidence, and that catalyze new partnerships and projects going forward. It also supports progress towards SPOR's intermediate outcome to improve the clinical trials environment in Canada.

"I do see a lot of duplication across the SPOR environment, and I think there's a big opportunity to consolidate and collaborate and make better use of our resources."

The SPOR Capacity Development and Patient Engagement entities, which have been funded more recently in 2019-20, best support achievement of more immediate outcomes given that limited time has passed since their implementation. The Capacity Development entity is intended to address gaps and areas of opportunity identified in POR capacity development in Canada, which facilitates the achievement of strengthening and maintaining the Canadian capacity in POR. The Patient Engagement entity plays a key role in ensuring patient engagement is achieved throughout all levels of SPOR. Together, SPOR's core elements are achieving SPOR's intended outcomes.

Many key informants (11/20) identified areas of improvement in SPOR design, including avoiding duplication and increasing communication. Instances of duplication exist primarily within the SPOR environment itself and include such areas as training, patient engagement frameworks, and evidence synthesis. Further, views among many key informants (11/20) on the connections or collaborations among core elements were mixed. Positive experiences (5/11) included connectedness among the Chronic Disease Networks and SUPPORT Units reaching out to iCT grant recipients. In contrast, negative experiences (6/11) included problems in communication and cohesion, recognition of too much siloed activity within and across SPOR elements, and that connections or collaborations among elements can be hit and miss.

Collaborations between CIHR and SPOR partners face some challenges.

While collaboration between CIHR and partners was generally reported to be satisfactory, challenges remain. The SPOR Summit, last held in the fall of 2018, was identified in program documentation as a key initiative that fostered collaborations between CIHR and SPOR stakeholders with the aim of exploring and sharing their experiences and knowledge promoting POR, highlighting early successes and lessons learned, and learning from experts on subjects such as patient engagement, SPOR capacity development, governance, and KT. Participants had the opportunity to participate in panel discussions, plenary and poster sessions, and network with others involved in POR. Though it aims to meet once every 18 months, the SPOR Summit has not met since 2018.

"I think we expected more guidance from CIHR on how to [compensate patient partners], as an overarching policy, instead of leaving all of us to our own devices to figure it out for ourselves…"

Many key informants (18/35) expressed satisfaction with the extent of collaboration with partners identifying the opportunities provided for connection between SUPPORT units and the platforms. Conversely, a few key informants (2/35) expressed some communication and partnership challenges, such as not having their work recognized or endorsed, or not understanding how best to work together.

From a patient partner perspective, many key informants (9/18) expressed satisfaction with SPOR patient engagement. At the same time, key informants offered several areas for improvement to collaboration, much of it centered on improvements to patient engagement. While considerations when paying patient partners in research are included within SPOR's Patient Engagement Framework, many key informants (9/18) repeatedly indicated a lack of harmonization or policy regarding patient compensation. These findings were consistent with evidence from the case studies that found that compensation practices appeared to vary across SPOR entities and projects based on difference guidelines and policies developed within the respective jurisdictions. In addition, a few patient partners (2/18) expressed the need for safe, supportive, and respectful environments to improve collaboration with recognition that researchers on occasion can be intimidating and unappreciative of patient involvement. A few key informants (3/18) also provided input on the need for CIHR improvements to coordination of operations in terms of consistency across the various elements of SPOR and CIHR.

Patient engagement does not adequately support recruitment of diverse patient partners.

SPOR's current approach to patient engagement does not adequately support recruitment of diverse patient partners, with some patient partner groups disproportionately underrepresented in SPOR research. Though there is evidence of incorporation of EDI and GBA+ considerations into the design of SPOR within program documentation, surveys and key informant interviews found a lack of diverse patient partner representation. Program documents revealed evidence of incorporation of EDI and GBA+ in the design of SPOR, research projects led by or involving Indigenous researchers and partners, integration of Indigenous methodologies into SPOR research, as well as research aimed at reducing gender disparities, and the involvement of Sex and Gender-based Analysis Plus (SGBA+) champions in core elements.

The Saskatchewan SUPPORT Unit reported engaging with Indigenous patients and family advocates throughout every phase of projects aimed at exploring health challenges faced by Indigenous patients. For example, the unit funded a project aimed at better understanding and advocating for Miyo-Mācihowin (good health and well-being) among Indigenous Peoples living with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. The Ontario SUPPORT Unit also reported engaging in several projects on Indigenous health, either led by or involving Indigenous partners. For example, two studies were conducted, one on the quality of end-of-life cancer care for First Nations people in Ontario and another on the health determinants and outcomes of Inuit living in Ottawa, Canada.

There were also examples of GBA+ incorporation in the design of SPOR core elements. Approximately half (five out of nine) of SPOR SUPPORT Units reported SGBA+ champions in the 2019-20 reporting year. The remaining SUPPORT Units intended to recruit a SGBA+ champion or partner to meet SGBA+ needs. Other SPOR core elements (i.e., Networks and Enabling Platforms) also have SGBA+ champions. For example, Can-SOLVE CKD, IMAGINE, CHILD-BRIGHT and DAC have established SGBA+ champions and the CPN has commenced addressing sex and gender in research with a SGBA+ champion who is a member of the Patient-Oriented Research Committee. These champions participate on working groups and work to integrate sex and gender considerations into research project design, analysis, and dissemination.

This was supported by SPOR stakeholders surveyed, in that they felt that the SPOR research project(s) they were involved in embedded EDI into all aspects of research to a moderate to great extent (M = 3.4, SD = 1.2, n = 154). Further, they generally did not report experiencing any EDI-related barriers (e.g., being a visible minority, gender, being an Indigenous person, or being a person with one or more disabilities) to participating in SPOR (Ms = 1.1-1.7, SDs = 0.6-1.0, ns = 6-175).

"Outside of Caucasian people, I don't see minorities, especially Indigenous people, plus people with one or multiple disabilities, being part of research projects in any way …I question the extent to which research projects have the diversity reflecting patients & families that use their healthcare services."

However, survey findings suggest a lack of diverse representation among patient partners participating in SPOR, and barriers to Indigenous partners participating in SPOR. Patient partner diversity, specifically the engagement of underrepresented patient partners, was the most frequently cited gap (n = 13) in SPOR identified by SPOR researchers (see Figure 4: Needs Not Addressed by SPOR Reported by Researchers). This was supported by the demographics of the patient partner sample obtained for the survey: patient partners who responded to the survey were Caucasian (87%, n = 34), women (62%, n = 24), and between the ages of 42 and 80 years old (M = 66.0, SD = 9.7, n = 36). Similar to the findings of this evaluation, Abelson and colleagues (2022) found that patient partners working across health system settings in Canada predominantly identified as female (77%), white (84%) and university educated (70%). The two patient partners surveyed who self-identified as Indigenous (100%, n = 2) reported experiencing barriers to participating in SPOR related to being Indigenous to a moderate extent.

Survey findings were supported by many key informants (15/32) who expressed concerns about the lack of diversity and inclusion, particularly the lack of engagement of racialized, Indigenous, disabled or other marginalized patient partners and that the majority of patient partners were older, retired, white women. Many key informants (15/32) also identified a number of GBA+ implementation challenges, mainly, the lack of diversity among patient partners (7/32) and that SPOR could do more to communicate GBA+ implementation guidance (7/32). For example, one patient partner described themselves as the only working age, male, disabled, and person of colour engaged in SPOR research and stated the SPOR is relying too much on the people who just happen to show up. Another patient partner noted that they were generally the only Indigenous partner engaged in the research. Some key informants (7/32) expressed that there was an opportunity to do more to improve the diversity and inclusion of patient partners by acknowledging that there is a problem and developing and communicating GBA+ implementation guidance.

SPOR's governance structure is not meeting its current objectives and lacks adequate patient partner representation.

SPOR's governance structure is not meeting its current objectives and lacks adequate patient representation. The NSC has not met since 2018 and a few key informants believed it generally provided advice rather than steering the SPOR program (3/22). Despite almost all key informants (19/22) attributing the NSC to providing advice to CIHR, having adequate representation, and the meetings being useful, the governance challenges identified overshadowed any of the past successes of the NSC.

"…going an unconscionably long period of time in the absence of governance, it effectively shuts out key stakeholders, including patients from governing… which is to me enormously problematic. This is not to take away anything from the excellence of the SPOR team… But you know they should not be managing SPOR by themselves… this needs to be co-created."

Many key informants (13/22) described the SPOR governance not working, confusing or absent as being very problematic. For example, key informants (13/22) described how it was not entirely clear how decisions were made as to the distribution of SPOR funding and that the governance structure did not do much in terms of oversight of the SPOR entities with major issues being left to the SPOR management team at CIHR to resolve. Some partner key informants (3/8) also expressed confusion about SUPPORT Units and Networks governance in terms of not knowing if partnering should happen with a Network or a provincial SUPPORT Unit or both. A few key informants (3/22) noted that oversight rested principally with the SPOR management team at CIHR without patient or partner representation. In addition, a few key informants (2/22) spoke to the challenges of working with different federal, provincial, and territorial health systems and that consideration needs to be given as to how provinces and territories influence the direction that SPOR takes. Most importantly, some key informants (6/22) indicated that the lack of representation of patients and partners in SPOR governance was a critical issue, particularly for a program with a goal to include the active collaboration of patients, providers, researchers and decision-makers.

Key informant interviews with experts from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Initiative (PCORI) and Consumer and Community Involvement (CCI) in Australia provided insights on the engagement of patients and partners in governance. Both PCORI and CCI have citizen or patient and other stakeholder representation on governance bodies. PCORI has patient representation and people with lived experience on the Board of Governors, various advisory committees, merit review panels in terms of assessment of applications, and peer review panels for when draft final research reports are produced, as PCORI is required by legislation to publish and make public as lay summaries all the findings from every funded research project. In comparison, CCI has consumer advisory group involvement in governance at the state and national levels.

There is an opportunity to inform an organization-wide patient engagement research funding model.

A comparative review of international POR organizations suggests that using SPOR to inform an organization-wide patient engagement research funding model, in which patient and public engagement in all research programs is either encouraged or mandated, could optimize CIHR's investments in SPOR.

"…we absolutely need patient oriented research and it actually needs to be above and beyond SPOR, it needs to be throughout everything that we do."

Currently, SPOR closely resembles PCORI in the United States, a specialized government research funding program for POR. PCORI key informant interviews revealed that PCORI's approach to public and patient involvement in research is at three levels – engagement with organizations, programs, and individual investigators, clinicians and patient partners or family members. In contrast, the CCI key informant described the approach in Western Australia to consumer and community involvement in research as primarily focused on capacity building and connecting people with lived experience with research opportunities. CCI has supported the grant review panel process to ensure that consumer and community involvement is an important criterion of the grant review scoring matrix for the National health and Medical Research Council and guidelines for public involvement in research have existed for a considerable period of time in Australia. Similarly, the Future Health Innovation Research Fund in Australia has recently mandated the involvement of the public and patients in research. These efforts have resulted in a rapid increase in CCI membership, from approximately 2,000 members 18 months ago to over 6,500 at the time of the interview (January 2023).

The comparative review revealed challenges among PCORI's specialized government research funding. With public and patient involvement being an unfunded mandate in PCORI's model, there are fewer resources to support and better understand public and patient involvement than if it were mandated. The lack of resources and mandate specifically for public and patient involvement means there is no way to ensure consistency and quality of involvement across PCORI; these challenges are similar to those faced by SPOR. Moving to an organization-wide model that mandates public involvement could address these challenges.

Further, an organization-wide model is more closely aligned with CIHR's new Strategic Plan than SPOR's current specialized government research funding model and would assist SPOR's progress towards achieving a cultural shift towards POR. CIHR's new Strategic Plan (2021-31) champions a more inclusive concept of research excellence that recognizes patients, the public, providers, decision-makers, and other users of research outputs as active collaborators throughout the entire research process. This strategy falls under Priority A of the new CIHR Strategic Plan to "Advance Research Excellence in All Its Diversity". Further, four key informants expressed views on alternative approaches to SPOR including the broadening of patient and public involvement in research beyond SPOR to all CIHR research funding opportunities. Almost all CIHR staff, SPOR entity leads and knowledge user key informants (14/17) interviewed shared thoughts on the evolution of SPOR that focused on the potential for informing and implementing POR across CIHR, the evolution of patient partners in decision-making, and the future sustainability of the SPOR Strategy. The CIHR Strategic Plan, evidence from the comparative review of organizations, and key informant interviews support an organization-wide patient engagement research funding model.

The previous evaluation's recommendations were not fully addressed.

The document review highlighted that according to the 2020-21 and 2021-22 annual updates to the SPOR Management Action Plan, only three out of the six recommendations made in the 2016 Evaluation of SPOR have been fully implemented. SPOR management state that they have fully implemented the evaluation's recommendations that CIHR should: 1) "increase efforts to strengthen SPOR's role in a common agenda for change to POR", 2) "provide strategic guidance regarding how SPOR elements are to work together toward achieving the Strategy's intermediate and long-term outcomes", and 3) "communicate plans for moving beyond the initial five-year funding period to manage sustainability expectations for CIHR investments in SPOR" and "provide clear communications regarding SPOR funding and options beyond the current five-year funding commitment to some elements". As of 2021-22, the remaining three recommendations from the 2016 Evaluation are partially implemented, with some steps taken towards full implementation.

There is limited evidence indicating that performance data are being used to inform decision-making.

There is limited evidence indicating that performance data are being used to inform decision-making regarding CIHR's implementation and optimization of SPOR. The first SPOR Evaluation, completed in 2016, recommended revising the initial SPOR performance measurement strategy to better measure impact in the second five-year cycle Evaluation of SPOR (CIHR, 2016). The strategy was revised with guidance from the SPOR WG and other SPOR stakeholders in April 2018. Given the partnered nature of the SPOR program, the SUPPORT Unit performance measurement framework and corresponding indicators were collectively built with the SUPPORT Unit performance measurement leads and approved by SPOR WG. The annual reporting template that is used to collect the data for these indicators is also revised with SUPPORT Unit performance measurement leads on an annual basis to reflect changing reporting needs. Based on the current document review findings, performance data are currently being collected annually from five out of the six SPOR core elements, including all SUPPORT Units, Networks, the iCT, the SEA, and the CDP, but there is limited evidence of how the performance data collected are being used for decision-making regarding CIHR's implementation and optimization of SPOR.

Challenges exist with the current management of performance measurement data.

Challenges exist with the current management of performance measurement data including lack of clarity regarding performance indicators, inconsistent or missing indicators, double-counting, introduction of new indicators at the end of the reporting period, burden, and lack of alignment of Network and SUPPORT Unit work plans with the reporting requirements developed by CIHR.

"…the metrics by which CIHR was trying to evaluate… some of them… did not actually make any sense for the model that we were [using] and some of the investments in the planning that B.C. had done."

In general, SPOR elements recognize the importance of performance monitoring for ongoing management of operations, planning and decision-making. However, the key informant interviews and review of documents revealed challenges associated with annual reporting and performance measurement including: lack of clarity regarding some categories of measurement (e.g., supervision versus mentoring activities); inconsistent or missing reporting categories (e.g., research professionals); double-counting and lack of clear guidance on how to avoid double counting; introduction of new reporting categories at the end of the reporting period; and performance reporting burden despite the process being co-developed by CIHR and the core elements. A few SUPPORT Units also stated that CIHR's reporting requirements do not align with their Unit's work plans and therefore do not capture the full range of SUPPORT Unit activities or their impacts. For example, an independent evaluation report commissioned by the Quebec SUPPORT Unit described the performance reporting experience as cumbersome.

Some key informants (7/20) provided comments regarding performance measurement in the context of the annual reporting process. A few key informants found the annual reporting process to be too burdensome (2/20) with no clarity on its use, not necessarily aligned to provincial and/or SPOR entity priorities (1/20), and that increased emphasis needed to be placed on measuring SPOR impacts (3/20) rather than activities or immediate outputs. Finally, one key informant commented that there is little reliability on how patient engagement is measured.

Performance

Key Findings:

- SPOR's core elements are contributing to the achievement of immediate outcomes, including the generation of new knowledge, infrastructure, capacity development and engagement of patients and stakeholders.

- SPOR is generating and disseminating new knowledge as evidenced by the number of KT products produced by the core elements based on the most recent annual report in scope of the evaluation (2019-20) and trends over the evaluation period.

- Research platforms and other types of research infrastructure are established by the SUPPORT Units, SEA and CDP.

- Capacity in POR is developed as evidenced by the 2,221 training activities reaching 37,429 individuals across the SUPPORT Units, Networks and SEA.

- While there is evidence of engagement of patient partners in all aspects of research, there are opportunities to improve the level of patient engagement in research to avoid the perception of tokenism.