Game changer: How an interactive video game is helping kids with disabilities improve their motor skills

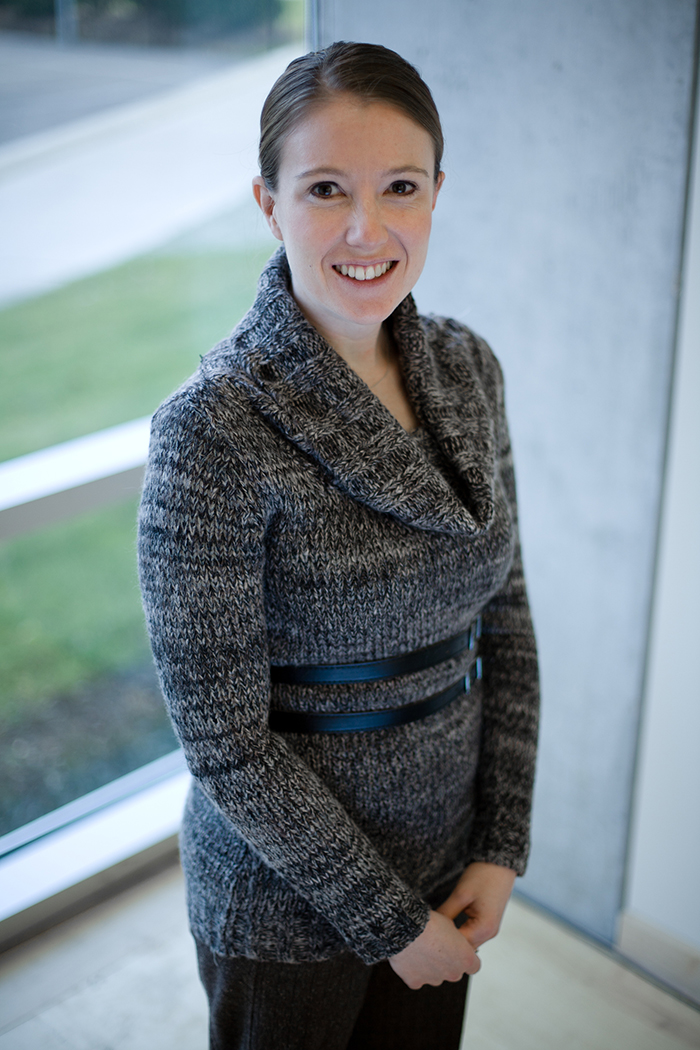

Dr. Elaine Biddiss, a scientist who designs technologies to help young people with disabilities, has no special interest in video games. But, a few years ago, when she saw how these games were engaging children at the Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital in Toronto, it sparked an idea. With the help of her research team, experts in video game design, clinicians, and patients themselves, she developed an interactive video game called "Bootle Blast" to help improve the motor skills of kids with physical disabilities like cerebral palsy.

Cerebral palsy (CP), a group of disorders that affects more than 80,000 Canadians, is the most common physical disability in children. CP affects people differently, ranging from weakness in a single hand to near complete loss of voluntary movement. Therapies, such as physical, occupational and rehabilitation therapy, can help improve motor function, but depending on provincial health plans and where families live, such therapies can be expensive and difficult to access. The repetitive nature of the movements can also be boring for young children, making it difficult to motivate them.

"It's a challenge for parents to do therapy with their child at home on top of all their other responsibilities," explains Dr. Biddiss. "That's one of the reasons why adherence to home therapy programs is very low. A lot of therapists and parents use entertainment videos, but they are not very adaptable to different abilities and therapy goals. We knew we had to try a completely different approach."

Improving motor skills through Bootle Blast

The video game Bootle Blast is actually a suite of 13 games centred around a robotic city where players are helping capture mini robots (the "Bootles"). In each of the games, the player's body is the remote control. Their movements are tracked using 3D sensors and a webcam, and are then mirrored in the game in real-time – making it particularly exciting and engaging for children. Dr. Biddiss describes the game as "mixed reality" since players interact with real-life objects in front of them, such as building blocks, while playing the games to improve their motor skills. As the player's movements are tracked and reflected on screen, the system measures the accuracy, frequency, and intensity of the movements and rewards the child for their efforts.

Each game has different therapeutic goals. When players cast spells with magic wands in "Wizard's Adventure," for example, they are moving their shoulders. When they race to the finish line in "Bootle Kart," they are practicing bimanual coordination. Other games target movements such as wrist rotation, elbow extensions, and grasping – and all with the interests of kids in mind.

"The clinicians at Holland Bloorview are very supportive of research, so they helped us recruit patients and families to try things out," Dr. Biddiss says. "We did a lot of play testing, and we consulted with kids with and without disabilities because they often play together. I'm not a video gamer myself, but I am a good listener – so my team and I took that feedback we heard and implemented it in a way that could help these kids."

On "Game Nights" at Holland Bloorview, kids would try out different mini-games and give the researchers valuable feedback. The team also set up Bootle Blast in the hospital playroom where siblings of patients might wait during appointments. This allowed researchers to see how kids with different abilities engaged with the game.

Building on initial success

The team has developed two versions of Bootle Blast. At the clinic, where patients are supported by therapists, the game is more focused on movements. In the "home" version, the movements are more integrated into the story arc to keep kids engaged. The team also made an important strategic design decision: users can't access all 13 games at once. Instead, as they play, users unlock new games, which provides the novel content that kids are craving and motivation to continue playing.

In their initial trial, the researchers set up the complete gaming system (with Bootle Blast and the 3D sensor) in the homes of five families who had a child with CP. "The outcomes were really positive in terms of sustaining their interest over the 12-week period," Dr. Biddiss notes. "It was too small a sample to be statistically significant, but we did see noticeable improvements in the use of the children's upper limbs."

Building on this initial success, the team has designed a clinical trial involving 46 children with CP aged 6-17 years. The children will be divided into two groups: one will play Bootle Blast at home for 12 weeks on their own, while the control group will continue with their usual activities for the first 12 weeks and then play the game for 12 weeks after that. At the end of the trial, Dr. Biddiss and her team will evaluate improvements to the motor skills of children in each group and collect feedback from them and their caregivers. The team will also examine if weekly contact with an occupational therapist made a difference to the family's experience with Bootle Blast.

"The design of this trial will give us a better idea of how Bootle Blast can be used – either on its own or in addition to traditional therapies – to help children with CP improve their motor skills and other functions," Dr. Biddiss says. "It will tell us whether it's enough to promote this video game for kids and families to use on their own, or whether use of the game needs some monitoring by a therapist to get the best results."

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced the team to revamp its plans for this trial, however. The pandemic made it difficult to recruit families in the first place, and it was no longer advisable for participating families to visit the clinic a number of times in person (which was part of the original plan). In response, they are rejigging the study to be carried out remotely.

"This could be a good thing," says Dr. Biddiss, "because now we will be able to test it with families in rural parts of Canada that may not have regular access to therapy services."

Commercializing the game

Even as the researchers work through the logistics of the remote trial, they are busy planning a new study that aims to enhance the commercial viability of the game. They will explore, for example, whether families can play the game on less expensive hardware or set it up in their homes without professional help.

The study will have two components. First, with the help of 12 children of diverse abilities, they will compare how well the game tracks movement with a low-cost, combined computer-depth sensor-camera versus a simple webcam. For the second component, they will test Bootle Blast in home settings with 60 children who have motor skill disorders. This test will run for 15 weeks and will allow the research team to assess issues like enablers and barriers to use and the perceived value.

"With this commercialization study, we're really excited that 15 of the 60 kids will be in rural areas of Costa Rica," says Dr. Biddiss. "These are families who have very little access to therapy services and who may benefit the most from this kind of system. It's going to provide us with rich data to understand what works with the system and what's difficult for families."

The study will also aim to understand how the team can make Bootle Blast even more engaging and accessible for children, adds Sharon Wong, director of commercialization for Holland Bloorview. "Regardless of how the clinical trial goes, this commercialization study will generate some insights about how the game is being used in homes, what the adoption barriers are, and how we can overcome those barriers to make the game even more engaging and accessible," she says.

Ms. Wong explains the data will also help bridge the so-called "Valley of Death" between developing great protypes and successfully launching a product on the market. To that end, the hospital has developed a spin-off company called Pearl Interactives to help commercialize the research and technology. It's through commercialization and meaningful partnerships with industry that Ms. Wong believes they can make sustainable positive impact.

Re-booting Bootle Blast

The research is now coming full circle. In the beginning, kids with CP who were playing entertainment videos, even if they had limited therapeutic value, inspired Dr. Biddiss to develop Bootle Blast. Now she's noticed that other kids without disabilities also enjoy playing the game. She hopes that in the future, games like Bootle Blast can not only provide fun opportunities for therapy, but also for inclusive play.

In clinics at Holland Bloorview, Bootle Blast has also been shown to be valuable for children with conditions other than CP. That sparked a new idea that is already gathering steam: adapting Bootle Blast for the needs of youth with spinal cord injuries.

"I'm an engineer, and my dream is to create technologies that go beyond research papers," says Dr. Biddiss. "For me, the story doesn't end until the technology is positively impacting families and their daily lives."

Bootle Blast evolves to meet the needs of youth with spinal cord injuries

In 2021, Holland Bloorview was a winner of the Spinal Cord Rehab Innovation Challenge prize run by MaRS and the Praxis Spinal Cord Institute. The $50,000 prize money will help the team tailor the motor skill-building in Bootle Blast for youth with spinal cord injuries. Like the original game, it will eventually be available both in clinics and at home.

- Date modified: