Passion and persistence: How fundamental research is addressing an aggressive breast cancer

Before Dr. Juliet Daniel became the pioneering cancer biologist she is today, she was studying medicine in hopes of one day becoming a doctor. But after several personal tragedies in her life, she realized she had a different calling.

"I came to Canada in 1983 to study medicine," she says, "but in my last year of my undergraduate degree, my neighbour back home in Barbados died of breast cancer. Just one month later, my mother was diagnosed with ovarian cancer. She passed away shortly after, and that's when I knew I didn't want to be a doctor – I wanted to be a scientist who could help find a cure for cancer."

More than 30 years later, Dr. Daniel is on her way to doing just that. As lead researcher in the Dr. Juliet Daniel Lab at McMaster University, she is working to understand the causes of – and find potential treatments for – an aggressive sub-type of breast cancer called triple negative breast cancer (TNBC).

Statistics show that her work is desperately needed. Despite increased awareness, therapies, and treatments, breast cancer remains one of the most common cancers worldwide, making up more than 12% of all cancers in 2020. It is also the most common cause of female cancer deaths globally.

What makes TNBC distinct, however, is that it has a higher mortality rate than any other type of breast cancer and has been found to disproportionately affect young Black women.

"In general, Black women are less likely to develop breast cancer compared to Caucasian women, but if they do develop it, they are more likely to develop TNBC," Dr. Daniel explains. "The challenge is that TNBC is far more aggressive and spreads very quickly to vital organs, and we don't currently have a targeted treatment for it. For now, treatment is limited to radiation and chemotherapy, which can be very hard on patients' bodies and may not fully eradicate the cancerous cells. For all of these reasons, it's been found that the women who develop TNBC are much less likely to survive it."

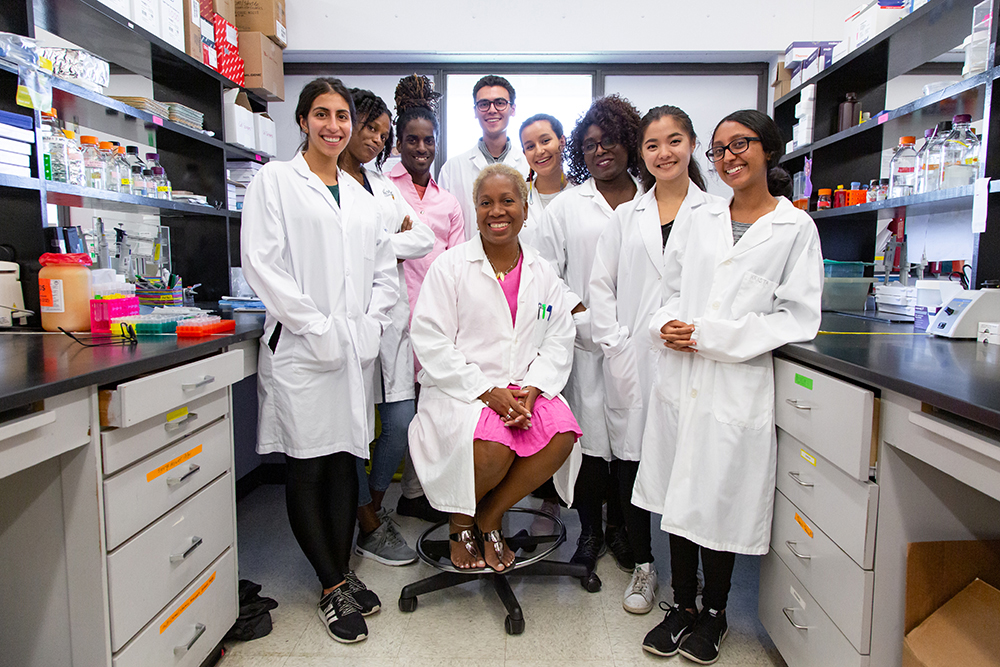

Backed by a team of multidisciplinary undergraduate, graduate and PhD students, Dr. Daniel's research is exploring why this specific type of cancer develops in Black women – and how we can prevent and treat it to save lives in Canada and around the world.

Fundamental research leads to a groundbreaking discovery

The mystery behind why TNBC disproportionately affects Black women has puzzled cancer researchers for years and is still not fully understood.

While some health conditions can be caused by social determinants (for example, food insecurity and low income can increase the risk of developing conditions like diabetes), previous research into TNBC hasn't found any obvious indications that it would develop more in Black women due to social or socioeconomic factors. This suggests it may stem from unknown biological and genetic factors that are passed down through generations.

In 2012, Dr. Daniel made a groundbreaking discovery that supported this idea. She found that a gene called 'Kaiso' – which she herself discovered and named back in 1999 – was highly expressed in breast cancer tissues in Black women compared to Caucasian women. She also discovered that women with high expression of this particular gene were less likely to survive breast cancer.

"At that time, my team and I were trying to understand why cancer spreads from one part of the body to another," she explains. "This was fundamental research, so we didn't know what results we would find or how they would apply to human health. But then we came across a study that was exploring whether this Kaiso gene was highly expressed in TNBC tissue – and it was! This got me thinking about whether there could be a relationship between Kaiso and the development of TNBC."

For the next several years, Dr. Daniel and her team started building on that study to test whether Kaiso played a role in the spread of TNBC in Black women. Without knowing what exactly their research would find, the team ran a series of experiments in which they reduced the expression of Kaiso in human TNBC cells, and then injected those Kaiso-depleted cells into the mammary fat pads of mice. When they did this, they found that the cancer didn't metastasize, meaning it didn't spread to other parts of the mice's bodies as it did in mice that were injected with human TNBC cells with high expression of Kaiso.

This discovery offered a valuable new piece of the puzzle: it suggested that Kaiso is a key contributing factor in the spread of TNBC through the body.

"Those findings were a game-changer for us," Dr. Daniel says. "Not only did it show us that Kaiso enables the spread and survival of TNBC cells, but it opened up possibilities for us to explore whether the same is true for other types of cancers. Plus, now that we know Kaiso supports the spread of cancer cells, that means we're one step closer to developing a targeted treatment that can deplete Kaiso and stop the spread of cancer."

Exploring new treatments to improve patient outcomes

Since the team's findings were published in 2017, Dr. Daniel has been busy exploring what a potential treatment could look like, as well as how Kaiso could be used as a prognostic or diagnostic tool in the meantime.

"Similar to the current approaches used in breast cancer genetic tests, looking at the levels of Kaiso expressed in women of African ancestry could help us determine whether they are at higher risk of developing TNBC, especially if they have a family history of breast cancer," she says. "This could help women make more informed decisions about their health and even save lives."

While the mystery still remains as to why Black women tend to have higher expression of Kaiso in the first place, Dr. Daniel and her team aren't giving up on their quest to find answers.

"Every day my team is running a series of molecular cell biology experiments and looking at the actual breast tumor tissues from Black women in West Africa or the Caribbean to understand how all of these factors fit together," she explains. "It's exciting work because we don't necessarily know where it will lead us or what we will discover –and yet, it's frustrating because in the meantime, women continue to develop and die from TNBC. This work is urgently needed, but it takes time, money, and resources. We can't cure cancer overnight, but we're doing our best to lay the groundwork."

When it comes down to it, Dr. Daniel's perseverance and passion stems from her personal experiences with cancer.

"Unfortunately, medicine couldn't save my neighbour or my mom in Barbados from dying of cancer all those years ago," she says. "I hope that one day, my work will help treat and save the lives of Black women and women of all backgrounds, not only in the Caribbean, but here in Canada and around the world."

Dr. Daniel's research has been supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, NSERC, CBCF/CCS, the Juravinski Cancer Foundation and BRIGHT Run.

- Date modified: