The Power of Health Research

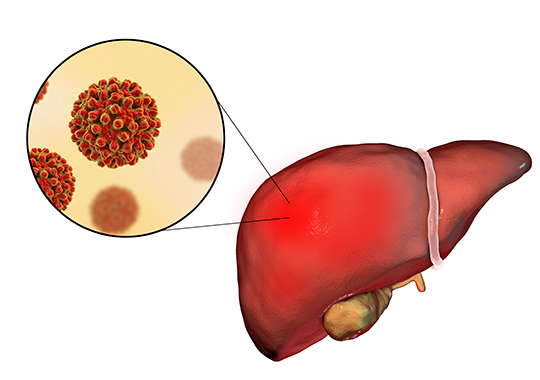

Canadian researchers working together to eliminate hepatitis C

July 28, 2017

Hepatitis C is a viral infection that attacks the liver, one of the abdominal organs that aids in digestion. It is regarded as a "silent" killer, as many people infected with hepatitis C feel no symptoms and are unaware that they carry the virus. Over time, some of these infected people will develop chronic hepatitis which can lead to liver damage, liver failure, and cancer.

It is estimated that about 400,000 Canadians are infected with the virus, or about 1% of our population. Globally, approximately 130-150 million people are infected, which results in an estimated 500,000 deaths each year.

The good news is that scientists have discovered a cure.

"The hepatitis C cure is a perfect example of how health research saves lives," said Dr. Naglaa Shoukry, a biomedical scientist at the University of Montreal Hospital Research Centre (CRCHUM) who has devoted her career to investigating this disease. "In just over 25 years, we have been able to discover the virus, clone it, figure out a way to screen our blood supply, and develop a treatment that can cure the disease. All of this happened as a result of scientific research, and many of the research milestones were achieved in Canada and through the Canadian Network on Hepatitis C."

As with most scientific efforts, the path to finding a cure often involved trial and error and building upon incremental improvements. In the early years, hepatitis C patients were injected with "interferon," a medicine that stimulates the immune system. Unfortunately, the medicine caused terrible side effects that often felt worse than the disease itself. The breakthrough occurred in 2010, with the discovery of "direct acting antivirals," drugs that directly attack the virus and remove it from the body.

Dr. Jordan Feld of Toronto's University Health Network has been treating hepatitis C patients for many years, and says the new drugs have been a game-changer.

"It has been revolutionary – and I don't use that word lightly," said Dr. Feld. "We've gone from cure rates of around 50% with drugs that have many side effects, to cure rates of 98-99% with one pill per day, for a few months, and no side effects. To be able to cure a chronic disease that causes such a huge public health burden is very gratifying, both as a doctor and as a researcher."

Challenges remain

Canada has set a goal of eliminating hepatitis C by 2030. However, while a cure for hepatitis C now exists, researchers are still faced with two big obstacles that must be overcome to end the disease.

The first challenge is to figure out how to get people into treatment. The second challenge is to develop a vaccine to prevent people from becoming infected with hepatitis C.

"We can cure almost everybody now, but one of the biggest problems with hepatitis C is that many people infected don't know they have it. People often don't have any symptoms until it's very advanced," said Dr. Feld. "So with our current research, we're trying to figure out ways to link people to care, as well as trying to develop a vaccine."

Recognizing the complexity of these two very different challenges, Canadian scientists from all areas – or "pillars" – of health research have joined forces to eliminate the disease.

The Four Pillars

The world of health research is comprised of four broad areas:

Pillar 1: Biomedical Research

Biomedical research seeks to understand how the human body functions at the molecular, cellular, and organ system levels. Through biomedical research, we are able to develop new therapies and medical devices.

Pillar 2: Clinical Research

Clinical research seeks to improve the diagnosis and treatment of disease and injury, and to improve our health and quality of life. Clinical research often builds on the work of biomedical researchers by testing new treatments on human patients.

Pillar 3: Health Services Research

Health services research seeks to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of health professionals and the health care system, through changes to practice and policy. It focuses on the social factors, financing systems, organizational processes, technologies, and personal behaviours that affect our health.

Pillar 4: Population Health Research

Population health research seeks to improve the overall health of different groups of Canadians by better understanding the ways in which social, cultural, environmental, occupational, and economic factors determine our health.

Getting people into treatment

Encouraging Canadians to get tested and treated requires the creation of new policies for provincial, territorial, and federal governments. This is where health services researchers like Dr. Mel Krajden of the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control are able to help. By collecting and analyzing data from Canadians with hepatitis C, these researchers can study how best to prevent new infections as well as care and treat those already infected.

"One of my interests has always been how big data can drive policy," said Dr. Krajden. "So through our CIHR-funded Canadian Network on Hepatitis C, I've been able to look at key health services questions, like: How can we use this data to create sensible policies that will both prevent infections and help sick people get the care they need?"

"It's wonderful that Canadians have a publically funded health care system, but health care is expensive. So, we need research to tell us what works and what doesn't," said Dr. Krajden.

Canadians with hepatitis C fall into two distinct groups.

The first group are Canadians who have a family doctor or who have access to clinics and care, and are able to get tested. This group is relatively easy to treat. It is also easy to obtain information on this group, which aids in developing policies to help them.

The second group are individuals who engage in high-risk activities, such as injection drug use. These people often suffer from extra vulnerabilities, such as mental health conditions. In addition, they often feel alienated from the health care system due to stigma or lack of trust. This group is not well represented in provincial databases, which makes the data incomplete. So we need extra effort to create solutions for these vulnerable people.

Population health researchers, like Dr. Julie Bruneau at the University of Montreal Hospital Research Centre (CRCHUM), are trying to fill in the missing pieces.

As a physician, Dr. Bruneau has spent the past 30 years treating drug users. As a researcher, she has studied this group and is able to contribute vital information to the databases. Her work will help prevent members of this disadvantaged group from falling through the cracks.

"Drug users feel ostracized from the mainstream clinical settings," said Dr. Bruneau. "In the coming years, if we want to eliminate hepatitis C, we will have to think about how to better care for this population."

While much work remains to improve support for vulnerable populations such as drug users, Dr. Bruneau has seen the profound impact that a cure for hepatitis C has had on her patients.

"Alcohol and drug addictions are very debilitating diseases in themselves," noted Dr. Bruneau. "In the past, we had to tell our patients: 'There's no cure for you… you need to stop drinking or using drugs.' Those messages are not very helpful in changing the behaviour of people who are already disenfranchised and have low self-esteem."

"But today, we tell them: 'We have a cure for your hepatitis C. It's very expensive medication, but we're going to prescribe it to you, because you're worth it!' And then, sometimes, you see something wonderful happen. You see their spirits rise. You see them become happier and more hopeful. And they start taking better care of themselves – they use less, they stop injecting, or they do good things for themselves. Those are the moments that I cherish the most as a physician and as a researcher."

Developing a vaccine

Of course, the ultimate prize remains the development of a vaccine, which could prevent the disease. Researchers in Canada, and throughout the world, are working toward this goal and are confident that it will one day be discovered.

"25% of infected people are able to eliminate the virus spontaneously with no drug treatment. So we're trying to better understand how our bodies mount this immune defence to prevent a hepatitis C infection," said Dr. Shoukry. "For a vaccine to be effective, it must protect the individual over the long term. So we're trying to find a way to replicate the same response that we see in people whose bodies naturally protect themselves from the virus."

"I have an incredible team working with me on identifying this protective response. In addition, we have the good fortune to work on this vaccine development project as part of a collaborative team led by the University of Alberta's Dr. Michael Houghton, the scientist who discovered hepatitis C, and Dr. Lorne Tyrell, another world renowned expert in this field," added Dr. Shoukry. "I am very optimistic about the future!"

Impact on Canadians

The impact of hepatitis C research has been far-reaching. It has provided Canada's health care system with the tools needed to diagnose the infection, a cure to treat those who are infected, and insights on the best prevention approaches. It has also provided provincial and territorial governments with the evidence needed to develop sound public policies, and contributed to health promotion initiatives throughout Canada.

Most importantly, research has saved lives and kept families together.

"I'd love for anyone who wants to see the impact of this research to just come to my clinic on any day," said Dr. Feld. "You'll see people who we've been treating here at the hospital for 20 years or more – people who have lived through the slow and painful experience of having their liver disease get worse and worse. Now they come in and we're telling them they're cured! At that moment, my patients often break down in tears. It's a very emotional experience for all of us. To be able to do this on an almost daily basis… it's difficult to express how gratifying it is. It really makes you want to get out of bed in the morning!"

Hepatitis C is just one example of how health research is changing people's lives. Through the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canada supports over 13,000 researchers who are strengthening our health care system and improving the health of Canadians.

- Date modified: